The Unpaid Workers who are Described as “Employed”

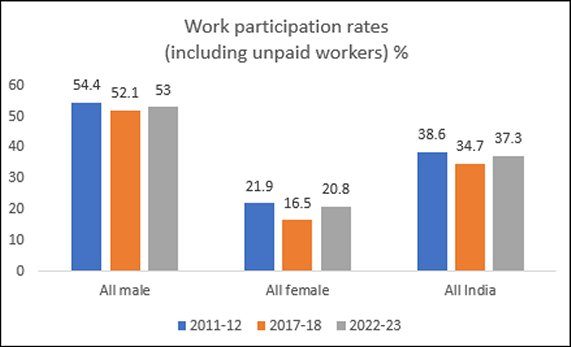

There has been much excitement recently at the supposedly significant recent increase in work participation rates in India, which is being heralded as a sign of the success of the current government’s economic policies. How significant is this increase in employment? The data from the NSSO (from the Employment-Unemployment Survey of 2011-12 and the Periodic Labour Force Surveys of 2017-18 and 2022-23) provide some indication, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Of course, these figures suggest that work participation rates in India are still very low by global standards, or even compared to countries at similar levels of development. The most striking feature is the extremely low recognised work participation of women, which is among the lowest in the world today. Yet even in this context, it is being argued that the recent increase augurs well for the future, because an increase in women’s work participation by more than 4 percentage points—which comes to an increase of 26 per cent—has occurred over a relatively short five-year period since 2017-18.

However, this ignores a significant issue with the way the Indian labour force data are presented, since those identified as “workers” or “employed” also include the category of “unpaid helpers in family enterprises”. This is a uniquely Indian way of dealing with data on work, in which such helpers are included in the “self-employed” even though they do not earn any income. This runs counter to the global practice which has been reinforced by the International Labour Organisation. This international usage clearly recognises that employment is only a subset of the broader category of work, which involves anything that provides goods or services for others or self-consumption, even when it is not marketed. By contrast, employment refers to only that part of work which is remunerated, either through wages and salaries or through earnings from self-employment. Therefore, in all other countries, those who do not receive any income are not counted among the employed.

However, in India, this specific category is still included in employment, on the grounds that it contributes to economic activity. But this is still a wrong argument: there is a lot of other work (such as providing goods and services like care activities to one’s own household) that is not classified as employment—in fact, the women who dominantly do that are actually described as “not in the labour force”.

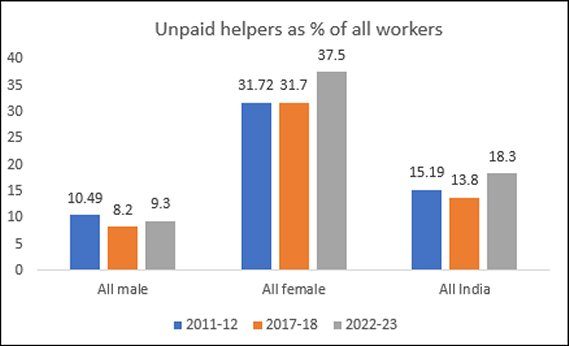

It could be argued that this inclusion of some unpaid workers in total employment may not matter very much, since such workers could be relatively few and stable over time. Yet that is not the case: not only are such workers very significant in proportion, especially for women, but also their presence tends to fluctuate over time. Figure 2 shows that even over the past decade, unpaid helpers in family enterprises came to a notable proportion of all those recognised as workers, and they increased in significance in the recent period 2017-18 to 2022-23. The increase was most marked for women workers, for whom the proportion of those who were unpaid went up by more than 18 per cent.

Figure 2.

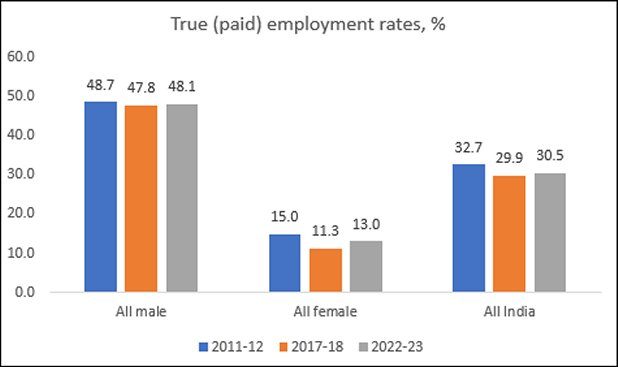

If we stick by the global definition of employment as referring only to paid work, then the actual employment picture looks even more dismal for India, with even less of an improvement over the recent period. Figure 3 provides the true paid employment rates, once those providing the unpaid labour are removed. The first striking feature is that actual employment rates are extremely low and have fallen over the decade, from 32.7 per cent to 30.5 per cent overall. Even more disturbing, the employment rates for women are even worse than those suggested by the official data—barely one in ten Indian women is engaged in some economic activity that provides her with an income. And this ratio has declined over the decade.

Figure 3.

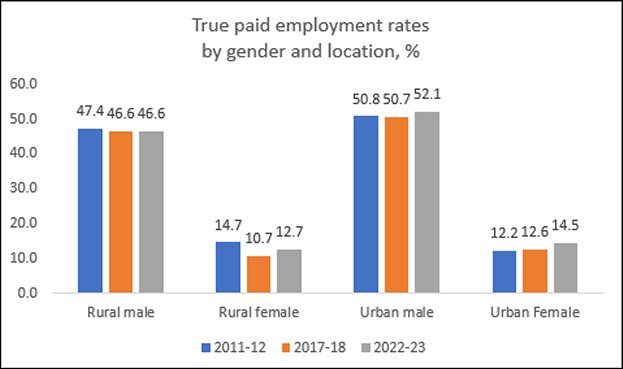

Figure 4.

Figure 4 provides a more detailed look at the same true employment rates, by location as well as gender. In rural areas, paid employment fell over the decade for both men and women, and the rural rates were shockingly low for women, on par with the urban rates that are widely recognised to be abysmally low. There has been a marginal increase in urban employment rates in the most recent period, but even so the employment rate for women is still below 15 per cent.

As always, the aggregate figures hide very wide variation across states, especially for women workers. There are some in which the share of women who operate as unpaid workers in family enterprises is relatively low. These are typically more urban states and UTs such as Chandigarh (2.8 per cent), Delhi (6.6 per cent), Puducherry (7.6 per cent)—but even Punjab has a relatively low incidence of such unpaid women workers at 9.4 per cent. By contrast, in some states, mainly in the Hindi heartland, most of the women who are classified as employed are actually unpaid, such as Chhattisgarh (62.2 per cent), Jharkhand (60.5 per cent), Rajasthan (56 per cent), Uttarakhand (55.5 per cent), Madhya Pradesh (53.4 per cent), Odisha (51.8 per cent), with Uttar Pradesh approaching that at 46.9 per cent. It is worth noting that these are states where the recognised work participation of women is already low—and even those recognised women workers are mostly unpaid!

Of course this points to the extremely dire employment situation in India, and it also highlights the need for abundant caution before celebrating any supposed increases in employment creation. A real change in this will necessarily require a job-centred economic development strategy, something that has definitely not been provided thus far.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on January 8, 2024)