Addressing Default: Lessons from an opaque experience

Around a month ago, The Reserve Bank of India, in a controversial circular, reversed its long-standing policy of not allowing banks to arrive at compromise settlements with willful defaulters or holders of fraudulent accounts. A willful defaulter is defined as “a borrower who refuses to repay loans despite having the capacity to pay up,” and, a fraudster as “one who intentionally cheats the bank with false documents/information and misappropriates the money.” Since the perpetrators of these criminal offences are clearly aiming to cheat banks of their money, they need to be proceeded under the law and their assets expropriated to give banks as much as the sums due to them as possible. A compromise settlement, on the other hand, is a negotiation-based agreement in which banks agree to forego a part of the sums legitimately due to them, in order to obtain some of the expected receipts and close the account at a loss. Since the intention of these borrowers is clearly to defraud the bank, that sum can only be a small proportion of the original loan and accrued interest, or the price that needs to be paid to escape the law.

The RBI once forced banks to reveal the bad loans they held and concealed in the name of restructuring. Clearly, it is now opting for this indefensible and controversial policy change that calls on banks to submit to pressures from rogue borrowers, only because it is being required to do so by a government from which it claims to be independent. The sums involved are not small. According to data from credit information company Transunion Cibil, between December 2020 and December 2022, the number of willful defaulter accounts increased from 12,911 involving a total sum of Rs, 2,45,888 crore to 15,778 accounts worth Rs 3,40,570 crore. That’s a 22 per cent rise in the number of accounts and a 39 per cent increase in the sums involved in a short two-year period. Corporate criminals seeking to defraud banks are displaying a new enthusiasm for their activity. Their confidence can only come from a belief that they can get away with it—an assessment that is validated by the RBI’s controversial circular.

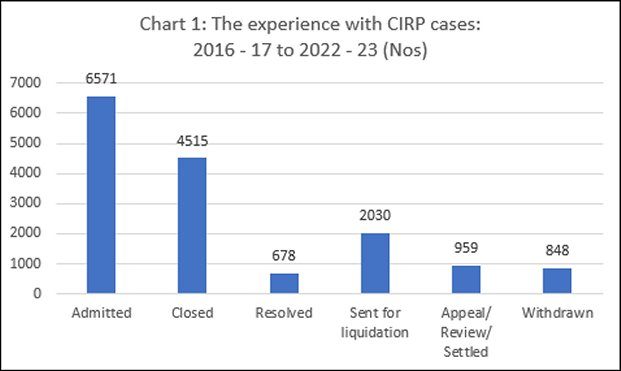

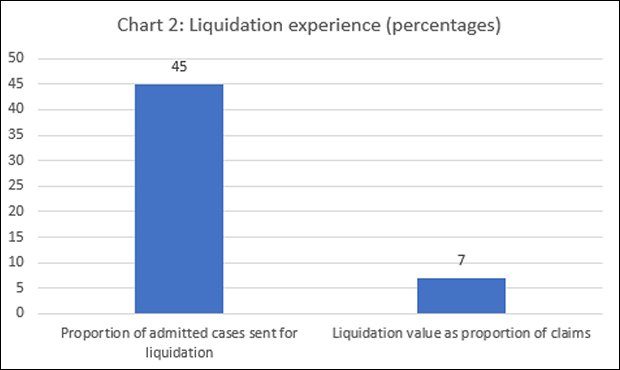

This accommodating stance of the government and the RBI has implications for an assessment of the role of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code of 2016. This has been indefensibly hyped as an effective mechanism to strengthen the position of banks vis-à-vis debtors and to reduce the non-performing assets (NPAs) on the books of banks with minimal losses. According to the most recent information available from the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India (IBBI), between 2016-17 and 2022-23 there were 6571 cases that were cleared for admission into the Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process (CIRP), of which 4515 have been “closed” (Chart 1). Of these, 2030 (45 per cent of the total) were not ‘resolved’ but sent for liquidation. In these (and other) cases, the original promoters had stripped or run down assets to a degree where the liquidation value was a mere 7 per cent of the claims of banks that had been admitted by the resolution authority (Chart 2). The long delays in sending the firms to liquidation, because of the delaying tactics of the promoters, only worsened the loss value. But the low recovery through liquidation is not so much an indictment of the CIRP as it is of the monitoring and reform of borrower activity by the banks, the RBI and the Finance Ministry.

Interestingly, even of the 2485 admitted cases that ‘escaped’ liquidation, only 678 have reached the stage of approval of a resolution plan. This 27 per cent success rate relative to cases that were not liquidated or 10 per cent relative to admitted cases is the not the only indication that the resolution process has been ineffective. The process continues to be slow, much as the cases dealt with earlier under the Debt Recovery Tribunal and SARFESI procedures. The IBC mandated that the CIRP should be competed in 180 days after admission, with allowance for a one-time extension of 90 days. This is a maximum limit of 270 days—but the 678 CIRPs which had yielded resolution plans by the end of March 2023 took an average 512 days to bring to conclusion.

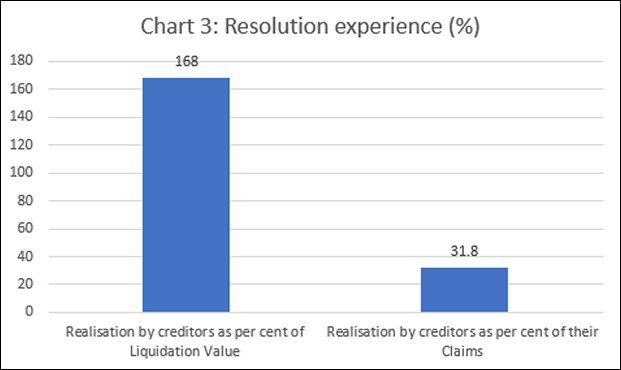

Even in the cases that moved to resolution, the average recovery or realization of claims by the financial creditors amounted to just 32 per cent (Chart 3). Even this figure was shored up by a handful of cases with good realization. In his statement on bank NPAs to the Parliamentary Estimates Governor in 2018, former governor of RBI Raghuram Rajan had reported that: “The amount recovered from cases decided in 2013-14 under DRTs was Rs. 30,590 crores while the outstanding value of debt sought to be recovered was a huge Rs 2,36,600 crores. Thus, recovery was only 13 per cent of the amount at stake.” If even in the small proportion of cases resolved through the CIRP the realization was 32 per cent, the IBC cannot be seen as a game changing transformation. The authorities underplay this aspect by referring only to the ratio of recovery to the liquidation value (a creditable 168 per cent) rather than to the ratio of recovery to the admitted claims from the banks, which is what is relevant for the banking system.

But that is not all. Discussions on the performance of the CIRP under the IBC miss the fact that of the 4515 cases that have been closed since 2016, closure was ensured in 959 cases (21 per cent) through Appeal/Review/Settlement and another 848 cases (19 per cent) were withdrawn by the creditor committee. This has to be seen in context. The declared stance of the government and the Reserve Bank of India is that the IBC process is meant to “rescue” corporate debtors. But that rescue effort is now being extended to willful defaulters and fraudsters, from whom the banks are likely to get little through a negotiated settlement. This suggests that the CIRP cases closed through negotiated settlement and withdrawal also did not yield much by way of recovery, relative to the claims of banks. The recovery sums in these cases are not available in official statements, since they have been taken out of the CIRP process. It is only if and when such information is made available and examined, that we would know the real extent of failure or not success of the post-IBC resolution process.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on July 10, 2023)