Panic about Petrol Prices

The latest IPCC report makes it clear: the planet is now dangerously close to a tipping point and reliance on fossil fuels has to be drastically curtailed and even fully eliminated soon, to avoid catastrophic climate changes. Obviously, this urgent call fell on deaf ears where it matters. It didn’t take long, or even very much, for world leaders—especially those who should really know better and have the means to do otherwise—to renege on their very recent pledges to reduce reliance on fossil fuels.

The latest excuse for avoiding the most basic inconvenient truths is the outcome of the Russian war on Ukraine. All it took was an increase in global oil prices and the (much faster) increase in retail oil and gas prices within the US for President Biden to release some of the US government’s strategic oil reserves, and even revive the possibility of importing from previous bete noires Venezuela and Iran. Now, the US administration will once again allow oil and gas leasing on federal land, thereby opening up more drilling for fossil fuels.

In Europe, which was extremely dependent on Russian natural gas and is now desperately seeking to diversify from it, the declarations are about shifting to renewable energy. But in practice, every country in the European Union has been left to choose its own path. Most have chosen to diversify their sources of fossil fuels, while some push for reviving and relying more on nuclear energy.

Political expediency clearly defines the knee-jerk response to higher oil prices, even though it runs completely counter not just to the promises made just a few months ago at the COP-26 in Glasgow, but also to the dire warnings issued by scientists. But is this knee-jerk policy response, especially in the rich countries, justified in comparative terms by the actual fuel prices prevailing in different countries?

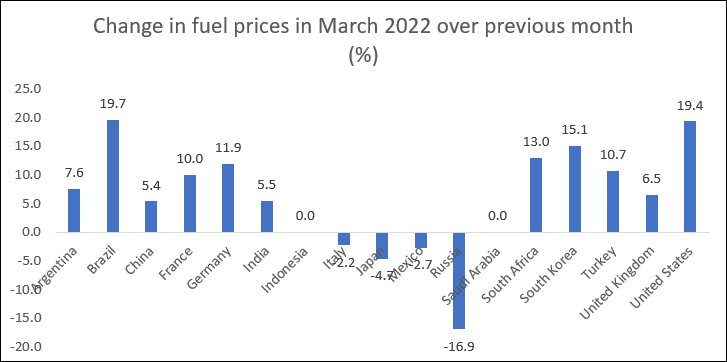

There is no doubt that oil prices have risen dramatically in recent months, with the Ukraine war, profiteering by oil companies and financial speculation all adding to the price pressures that were already evident before the war. Figure 1 indicates how rapidly prices have gone up in some major economies in the month of March 2022 alone, just compared to the earlier month. Some countries like the US and Brazil have experienced dramatic increases of nearly 20 per cent, coming on top of an already rising price trend.

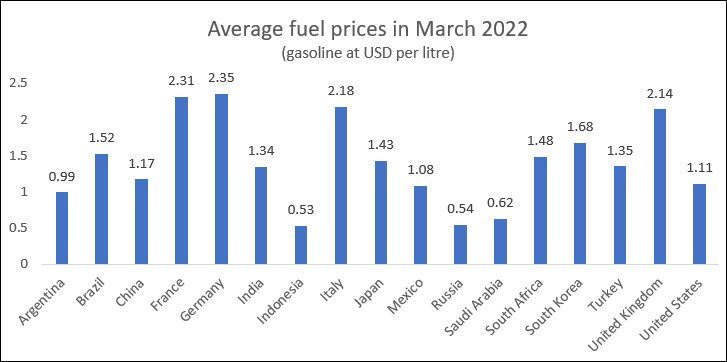

However, the recent inflation does not give an indication of the extent to which actual fuel prices vary across countries. Figure 2 provides data on average price of gasoline per litre in some of the same major economies (mainly G20 countries). The differences are stark: European countries like Germany, France, Italy and the UK show significantly higher absolute prices than oil producers like Saudi Arabia and Indonesia, while most low to middle income countries have fuel prices somewhere in between.

Figure 1

Source: https://tradingeconomics.com/country-list/gasoline-prices

Source: https://tradingeconomics.com/country-list/gasoline-prices

Figure 2

Source: https://tradingeconomics.com/country-list/gasoline-prices

Source: https://tradingeconomics.com/country-list/gasoline-prices

The variations in absolute fuel prices across countries shows clearly that the global oil price can explain only a part of the rising price trend. It is also worth noting that some countries like India show higher absolute petrol prices than the US.

While the cost of crude oil is obviously the largest element of the retail price of petrol, the retail price is significantly affected by taxes and subsidies, the costs of refining and transporting and the associated profits margins and commissions. In late March 2022, the price of West Texas Intermediate crude oil, at around $120-121 per barrel, was effectively $0.75-$0.76 per litre. The variations in prices from that global price therefore show the extent to which these different forces together play a role in price determination of petrol in these countries.

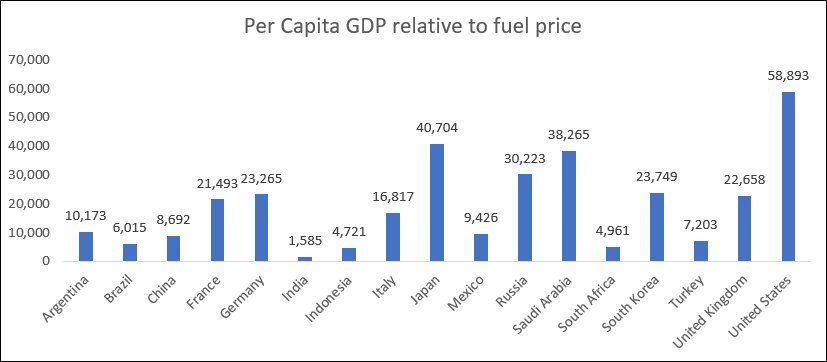

Figure 3

Source: https://statisticstimes.com/economy/countries-by-petrol-prices-and-gdp-per-capita.php

Source: https://statisticstimes.com/economy/countries-by-petrol-prices-and-gdp-per-capita.php

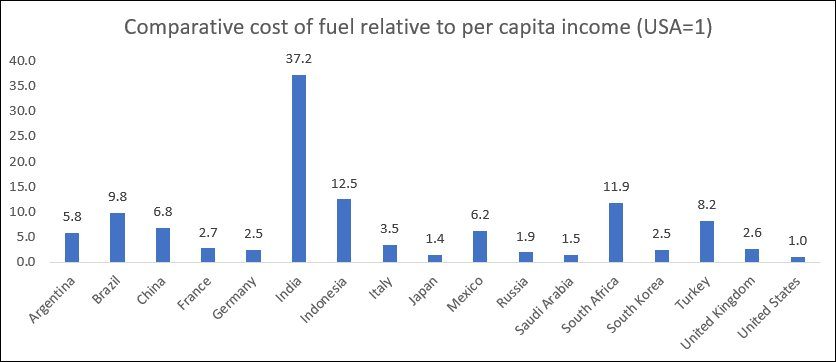

Figure 4

Source: https://statisticstimes.com/economy/countries-by-petrol-prices-and-gdp-per-capita.php

Source: https://statisticstimes.com/economy/countries-by-petrol-prices-and-gdp-per-capita.php

However, this still does not reveal the true cost of retail petrol in these countries, which must obviously be seen relative to purchasing power. In the absence of other more reliable indicators such as average household consumption or median wages, we take per capita income (in USD at Market Exchange Rates) as a proxy. Figure 3 shows that the per capita income (in USD) relative to the fuel price per litre has a very different pattern from that of absolute price. Here the rich countries—most of all the US but also countries in Europe show much higher numbers, indicating that retail petrol prices account for a much smaller burden in these countries.

The United States clearly outstrips all other countries in this regard, with per capita income at a level nearly 60,000 times the retail petrol price per litre. Meanwhile, some middle income countries, like Brazil, South Africa and India, have much lower such ratios. Of course, in each of these countries, the internal income inequality implies that the real burden on the poor is much greater.

Figure 4 tries to present this point in another way, by taking the relative retail price of petrol in the US (relative to per capita income, that is) as the base to compare with other countries. This brings out starkly just how cheap petrol really is in the United States. It shows that the relative price of petrol in India is more than 37 times that of the US, in South Africa nearly 12 times and in Brazil nearly 10 times. Even in China, this ratio is nearly 7 times that of the US. By contrast, rich countries like Japan, France, Germany, Italy and South Korea, are much closer to the US.

Even this very basic comparison shows that extent to which people in much poorer countries already have been paying relatively much higher prices for their petrol—with consequent effects on all other prices sin e fuel is a universal intermediate. In this context, the massive outcry about higher fuel prices in the rich countries, and especially in the US, is not just surprising, but one more indication of the pervasive and egregious double standards prevailing in the rich world.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on April 18, 2022)