MNREGA under the Modi Regime

It has been clear for some time that the NDA-led central government is not particularly mindful of its legal obligations, particularly where rights-based laws are concerned. There has been continuing and blatant violation by the central government of Supreme Court requirements regarding anganwadi centres, as well as of the Right to Education Act and the National Food Security Act. This has essentially occurred primarily through budgetary under-provision, and then further cutting down of the financial outlays necessary to meet the requirements for proper functioning of these programmes. But even in this sorry context, the treatment meted out to the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MNREGA) stands out in terms of the shoddy treatment it has received.

Let us remind ourselves: when the MNREGA was passed in 2005, it was passed unanimously, with all parties agreeing to it, even the BJP and other current constituents of the NDA. The Act quite clearly specifies that its functioning must be demand-driven, with demand for work from rural households (up to the specified limit of 100 days per household) driving the setting of up public works, and with the financial flows required to sustain these automatically flowing from central to state governments. Procedures for ensuring this were clearly laid out in the Rules and Guidelines. Indeed, the earlier Guidelines made it clear that once 60 per cent of the funds already disbursed had been spent in a state, the next round of transfers should be made, so as to prevent any stoppages or delays.

So the idea of having limits to the central government spending under MNREGA is bizarre – but more importantly, it is also illegal because of the very nature of the ACT. Yet caps on spending on this programme were evident even under the previous UPA government, as the UPA Finance Minister P. Chidambaram began to cut the outlays for it. Under the Modi regime they have become the norm, to the point where Finance Minister Arun Jaitley appeared to find nothing wrong in declaring when he presented his annual Budget for the year, that he would provide an additional Rs 5,000 crores above his declared outlay on the programme if tax revenues go up sufficiently. This was of a piece with the contempt for the MNREGA displayed by Prime Minister Modi on the floor of Parliament, when he famously declared that this was a monument to the previous government’s failures.

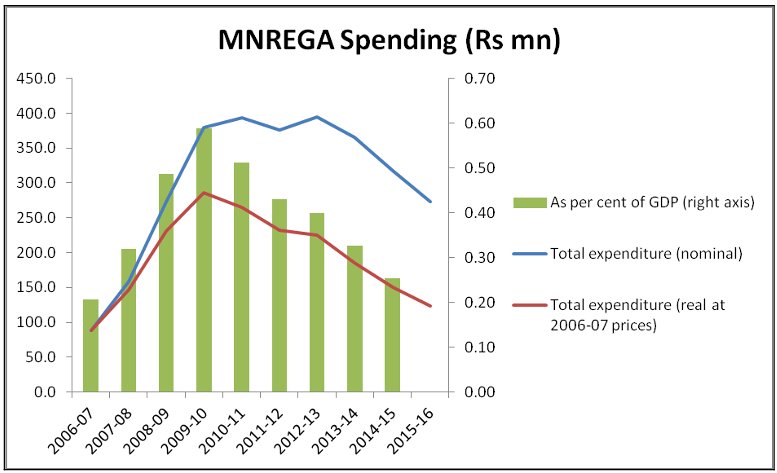

This appalling disregard for the central government’s legal obligation has been associated with significant reduction in outlays. As it happens, the MNREGA in general has been in effect much cheaper for the government than the projections before the law were implemented would have suggested. As Chart 1 show, total spending on this programme grew in nominal terms until 2010-11, as the programme was being rolled out in the various districts across the country and beginning to find some stability. Thereafter, however, it has declined even in nominal terms. In real terms, that is, deflated by inflation as measured by the CPI-AL, it has declined much more sharply, while the spending has dropped precipitously in terms of share of GDP.

Chart 1

This has been done by restricting the flow of funds from centre to states, such that states end up with pending obligations that are carried over into the next financial year. In the current financial year, for example, 18 per cent of the budgetary outlay was required simply to meet the pending obligations of the previous year. This is typically associated with significant amounts of unpaid wages – so that delayed wage payments had become a major bane of the programme. State and local governments in turn avoid setting up more works because of the inability to fund them, and restrict the “demand for work” by the simple expedient of not accepting or recording such demand until funds are available. In any case, where wage payments have been significantly delayed (in some instances for a year or more) workers themselves are less likely to be interested in seeking work under it. So a programme that was explicitly designed to be demand-driven has now become entirely determined by the outlays made available by the Centre, and these have become more niggardly over time.

The first year of the NDA regime was the most striking in this respect, as Chart 1 indicates. The apparent revival in MNREGA spending in the first half of the current financial year, which has been much advertised by the government, has to be seen in this context, as the levels of spending in real terms – even if they were to be maintained for the rest of the year at the same rate – would still be less than in previous years like 2010-11.

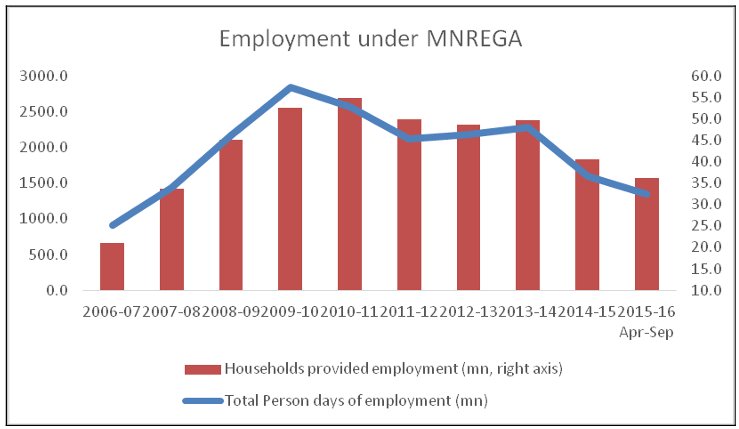

This obviously has direct effects on the viability of the programme and its effectiveness. Chart 2 shows how the impact of the programme in terms of employment generation has been affected by the cutback in funds. The number of households that benefited from this programme peaked at 55 million in 2010-11, while the person days of employment generated peaked at 2.8 billion in the previous year, 2009-10. Even at that peak, the programme was nowhere near providing the promised 100 days of work per household – instead the average across the country was only 54 days per household. This too has fallen since then, so that in the past few years the days of work per household under the programme have been less than 40.

Chart 2

This is the context in which the latest drama around the MNREGA is being played out. As mentioned earlier, 2014-15 was a year when the funds where cut sharply and the states were denied the funds essential for sustaining the programme. It got to the point where the Chief Minister of Tripura, the best performing state in recent years, was actually forced to come and sit on a day-long dharna in Jantar Mantar in New Delhi, demanding that the Centre fulfil its legal obligation of providing the money for this programme to run! Even such a desperate measure had little impact on a Modi government that in its first year was flush with the arrogance of power and complacent in its perception of getting away with whatever it wanted.

However, 2015 was a sobering year for the central government and for the BJP in particular, framed by two significant electoral defeats in state assembly elections in Delhi and Bihar and marked otherwise by inability to pass its desired laws in Parliament or to do much else of real substance. It was also a year in which agrarian distress became widespread once again, after a period when it had been on the decline. The increasing difficulties faced by farmers and the impact of declining real wages in rural areas of most parts of the country were significant enough to come to wider public attention.

It is possible that even in BJP-ruled states, the positive role played by the MNREGA in stabilising rural incomes and providing crucial sources of demand for the economy were becoming evident. This may be why, after the first quarter (April-June 2015) when the central government continued its cynical approach towards the programme, there was an apparent reversal in the second quarter. More funds were released in the July-September quarter, and this had an immediate and strikingly beneficial impact in terms of reducing delays in wage payment and enabling local governments and panchayats to set up more works. So the second quarter, which is normally not a period when much MNREGA works have been set up in the past as it is the period of monsoon and sowing, became one of sudden dynamism. While data on the third quarter are not yet available on the official website, it is possible that this dynamism continued into the third quarter, as suggested also by field reports.

The very fact that the mere release of more funds from the centre to the states could have such a positive effect shows how much huge pent up demand for the programme exists across the country, and the extent to which the MNREGA was been wilfully suppressed by the central government in complete defiance of the law. Yet this improvement could have been another flash in the pan, a temporary spurt of enthusiasm from the government that still remains fundamentally uncommitted to it.

This becomes clear from letters accessed by activists Aruna Roy and Nikhil Dey using the Right to Information Act, written by the Ministry of Rural Development to the Finance Minister. The letters are actually damning in establishing the proclivity of the Finance Ministry to curb this spending and deny the legal requirement of making funds available. The two letters written in late December 2015 by the Minister and the Secretary of Rural Development, both make the point that 95 per cent of the funds provided for the entire year had already been spent, and the programme would effectively come to a halt unless additional money is provided immediately.

The letters note that the Ministry has received a number of requests from state governments, not only for additional spending but simply to meet pending liabilities. (Obviously these request received in the previous months could not be responded to because the Ministry itself was not given the requisite funds.) The letters point out that the government’s own declaration that the days of employment provided per household could be increased to 150 in the six drought affected states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Telengana and Uttar Pradesh, would likely lead to further spending in these states. (It is ironic that some of these states are among those already in deficit, and with no money at all to spend on the programme.)

Despite all this, until the first week of January 2016 the money had not been forthcoming – not even the additional Rs 5,000 so “generously” promised by Mr Jaitley, which he clearly ought to provided done since tax revenues were already higher than expected. It may well be that the public outcry generated by the media exposure of these letters and related facts will force the Finance Ministry to release at least this amount to the Ministry of Rural Development and thereon to the states. But it is still appalling that such public discussion and outcry is required before the central government does what it is legally obliged to do. And the danger remains that without constant pressure of this sort, it will once more backslide and seek to cut down on this programme.

This is probably not surprising given the general orientation of this government, but it is both politically and economically stupid. Politically stupid because, in a context of continuing rural distress and lack of productive employment opportunities, the constituency demanding such employment is huge and even extends beyond direct beneficiaries to those who would indirectly benefit from it. Economically stupid because, in an economy in which there is precious little happening in terms of demand generation, investment rates are also low and even the corporates are now demanding more fiscal stimulus. MNREGA spending is known to have large multiplier effects that create increases in rural income well beyond the actual spending because those who receive the wages spend more locally and therefore it can stimulate what is once again a depressed rural economy. Sad indeed that a programme with so many positive effects still has to be fought for at every turn.

(This article was originally published in the Frontline, Print edition: February 5, 2016)