India’s Collapsing Exports

As the Modi government completes two years in office, one of its major economic programmes—the Make in India initiative—that promised manufacturing growth based on exports, is staring at failure. According to the most recent monthly figure available at the time of writing, in April 2016, India’s merchandise exports stood at $20.57 billion. That was 6.74 per cent lower than where it stood in the corresponding month of 2015, marking the 17th consecutive month when India’s merchandise exports valued in dollars had recorded a decline relative to the previous year. The export downturn during this 17-month period was worse than even what the April figure suggests. Over the fiscal year 2015-16 (April-March) for example, which covers 12 of those 17 months, merchandise exports were down 15.85 percent in dollar terms at $261.14 billion, compared with $310.34 billion in 2014-15.

The most obvious explanation for the decline is the sluggish state of world demand ever since the crisis of 2008-09, which has affected all countries adversely. That is an explanation the government is quick to advance, since it absolves domestic policy of all responsibility. Rita Teaotia, Commerce Secretary, reportedly said: “Exports have been declining and this is a part of the global slowdown in trade. We are very much part of that. If the slowdown in India is different from what is happening in the rest of the world then we would have been alarmed.”

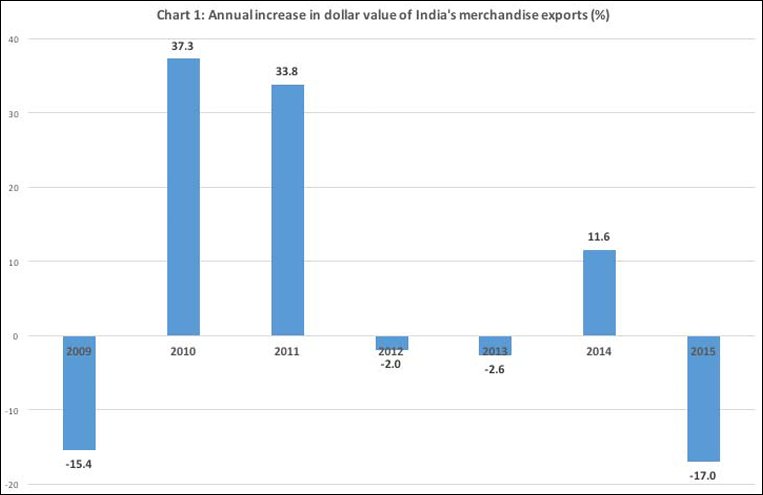

But that argument ignores signals coming from more detailed evidence. India’s export performance was not as bad in the period after 2009 as a whole as it has been over the year and a half ending April 2016. If we take figures for calendar years 2009 to 2015, the annual, year-on-year growth of exports was the worst in 2015. The 17 per cent decline during 2015 was even higher than the 15 per cent decline recorded in crisis year 2008 (Chart 1). Moreover, the annual average growth recorded over the six-year period 2009-2015 was a respectable 10 per cent. While volatility in oil and commodity prices explain some of the differences in annual growth rates across time, it cannot be denied that export performance has taken a turn for the worse over the last year and a half.

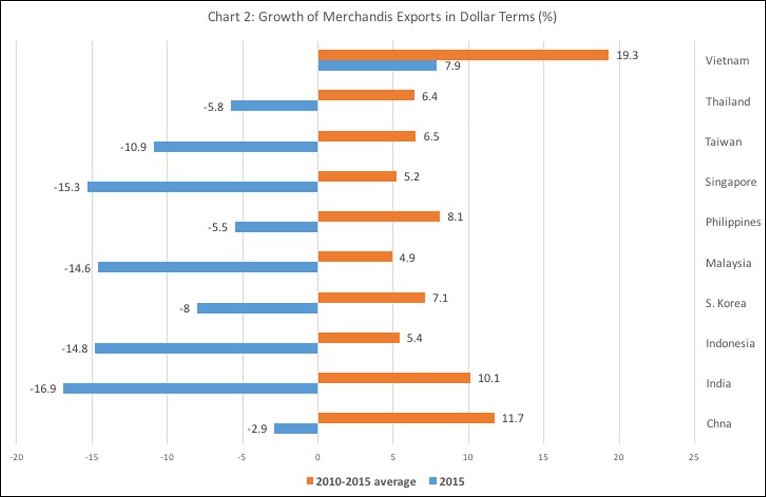

But that is not all. The downturn in India’s export performance during 2015 seems sharper than that experienced by many of its Asian neighbours, whom India is seen as competing with to win space in global markets. In fact, if we take the average year-on-year rate of growth during 2010 to 2015, India was the third best performer on the merchandise export front after Vietnam and China. On the other hand, while all countries recorded a much lower rate of export growth in 2015 as compared to the average rate over 2010-2015, India was by far the worst performer in terms of the extent of the export growth reversal in 2015 relative to the medium term average (Chart 2). So the argument that India’s record is only a reflection of trends in other similarly placed economies also does not hold.

For the Modi-led government with its Make in India hype, the fact that the export downturn has coincided with much of its term in power is indeed an embarrassment. So is the fact that India’s performance in this period, though reflective of global trends, was much worse than elsewhere. Mere denial does not make the evidence disappear. What explains India’s poor performance even relative to comparable countries?

If we turn to more disaggregated product groups to find an answer, it emerges that the range of commodity groups that have recorded negative export growth in fiscal 2014-15 is rather wide. While sluggish global demand played a role in all instances, in some cases India-specific factors had an important contribution to the export decline. A sample of commodity groups where the decline in exports was significant (more than $ 1 billion) includes oilmeals, iron ore, engineering goods and petroleum. There were other areas, especially pharmaceuticals where, even though rates of growth of dollar export values were positive, they had fallen from 25.7 per cent in 2011-12 to 3.3 per cent in 2014-15.

Clearly, very different factors could have played a role across these groups. Consider oilmeal (used as feed in poultry, cattle and fish farming) for example. India has for some years now been a significant exporter of oilmeal products. But recent poor or indifferent monsoons have adversely affected domestic oilseed output. This not only reduced the surplus of domestic supply relative to demand that could be released for export, but also raised domestic prices at a time when global demand conditions were depressing prices charged by India’s competitors. The net result was a shift away from Indian oilmeal in global markets. Expectations are that, with domestic demand rising, India would turn a net importer of oilmeal in the near future. Thus, domestic factors intensified the outcomes deriving from global trends.

Similarly, while the immediate drivers of the 2015 iron ore export decline are external, with the sharp fall in Chinese demand and over expansion of capacity by global majors (such as Vale, BHP and Rio Tinto) having an important role to play, there are medium term domestic factors that worked to reduce the value of exports from close to $6 billion in 2009-10 to just above $500 million in 2014-15.

Earlier, global demand conditions had encouraged a sharp increase in iron ore exports from India. When the volume of iron ore exports soared, domestic manufacturers of steel were hit by supply shortfalls of iron and a rise in prices. This was only worsened by a Supreme Court verdict banning iron ore mining in Goa for environmental reasons, which was, lifted only in 2014. The government’s response to the iron ore shortage for domestic producers was to impose an export duty on ore exports which was raised sequentially from 5 per cent in 2008-09 to 30 per cent in December 2011. This affected exports adversely, bringing it down from 117.37 million tonnes in 2009-10 to 14.42 million tonnes in 2013-14. Though over the last two years, duties have been reduced to revive exports, which the government is now desperate to promote, these efforts have not yielded results with global demand conditions having worsened hugely even as global capacity expanded in the interim. In sum, well before the recent downturn in iron ore demand and prices, the domestic economic and environmental effects of indiscriminate mining to earn export revenues had already scaled down the volume and value of iron ore exports from India. This trend has only continued in recent months.

An interesting case is that of pharmaceuticals. India’s pharmaceutical industry, which had benefited from the absence of product patents till the revision of the patent law in 2005, had acquired significant strengths in the manufacture of generic drugs that are substitutes for more expensive branded products. Exercising that strength the industry had built up a position in the market for drugs for which the period during which patent protection applied had expired. The generic drug market is estimated to account for around a third of the $1 trillion plus global market for pharmaceutical products. India was seen as a major beneficiary, and this was reflected in export growth figures during the years ending 2011-12. But as noted earlier those growth rates have collapsed more recently.

One explanation for this decline is the changing structure of the industry. While on the supply side the generic drug industry is highly competitive with a large number of producers of varying sizes, there is growing consolidation of the distribution business in the world’s largest markets, especially the US. This is driving down prices in many areas, affecting export revenues adversely. Further, drug multinationals, which are striving to retain market share by introducing newer, patented (but not necessarily novel) substitutes for their drugs going off patent, are pushing to rein in imports from generic drug exporters in countries like India. They are pressuring their governments, especially in the US, to tighten regulatory standards that can result in a ban on particular exporters from abroad either on the grounds that they do not meet the purity and strength standards of the branded ‘original’, or that production and testing conditions of the drugs concerned do not meet required developed-country quality standards.

In practice the line separating warranted as opposed to purely protectionist application of such standards is increasingly blurred. The result has been forced withdrawal of some Indian exporters from some markets. To top it all, the US government has recently made it mandatory for producers of formulations in that country to procure Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) domestically. This would mean that producers in the US who were acquiring their APIs or bulk drugs from producers abroad to produce formulations at home cannot continue to do so. India was an important supplier of such bulk drugs. More recent development such as the collapse in commodity prices, the global recession, and the resulting sharp depreciation of currencies have only intensified this process of market contraction for producers from India who are also disadvantaged by a relatively stronger rupee.

Finally, the most curious case is of course crude and petroleum products. For long India has been importing crude and petroleum products because, its requirements have far exceeded domestic production. Crude is imported and refined domestically and to the extent that some petroleum products thus obtained are in excess of the domestic demand for such products after accounting for imports, the balance is exported. This has had two effects. The first is that if only petroleum products are considered India has been a net exporter since the early 2000s, as refining capacity increase took supply (production and imports) beyond domestic demand. But India is a large importer of crude so that when crude and petroleum products are considered together India is a net importer in this product group.

However, as India’s demand for petroleum products have grown, the volume of export has fallen from a peak of 67.9 million tonnes in 2013-14 to 60.5 million tonnes in 2015-16, even as imports of crude rose from 18.9 million tonnes to 20.3 million tonnes. India’s net export of petroleum products (after adjusting for imports) fell from 51.1 million tonnes in 2013-14 to 32.2 million tonnes. This was, however, occurring at a time when the international prices of crude and petroleum products were falling steeply. The average price of the basket of crude imported by India fell from $105.5 per barrel in 2013-14, to $84.16 per bbl in 2014-15 and $46.17 per bbl in 2015-16. Associated with this sharp decline in crude prices has been an equally sharp decline in international prices of petroleum products. This has resulted in a collapse in the value of petroleum product exports from $60.7 billion in 2013-14 to $47.3 billion in 2014-15 and $27.1 billion in 2015-16. That too has contributed to the fall in the dollar value of merchandise exports, though it is not the sole or even principal cause of the fall as the government seems to argue.

Thus, a combination of factors—India’s continued dependence on traditional exports including oilmeal, domestic policy, protectionism abroad, and a distorted dependence on export revenues from an area like petroleum and products where India is a net importer overall, besides sluggish global markets, excess supply, and the loss of India’s competitiveness due a relatively stronger currency, explain the downturn. These are not factors that are all temporary. They reflect deeper structural weaknesses in the composition of India’s exports. What that suggests is India would do well to focus on structural changes supported by its domestic markets that build new dynamic comparative advantages rather than plead that transnationals should come and Make in India so as to push growth without generating balance of payments problems.

(This article was originally published in the Frontline, print edition: June 10, 2016)