India’s China-trade Challenge

It was headline news when Chinese customs statistics at the end of September 2022 indicated that for a second calendar year, India’s trade with China would settle at well above $100 billion. That was only partly because of the positive implications of burgeoning trade between the two countries that only two years back were involved in clashes at the border at Galwan. The bilateral trade balance attracted attention because it reflected large imports from China into India, many multiples of India’s exports to China. Over the first nine months of 2022, China’s exports to India rose more than 30 per cent to $89.7 billion while India’s exports to China fell 36 per cent to $13.97 billion. As a result of this almost one-way trade flow, the aggregate bilateral trade flow (imports plus exports) of $104 billion over those nine months resulted in a deficit in trade for India vis-à-vis China of $76 billion.

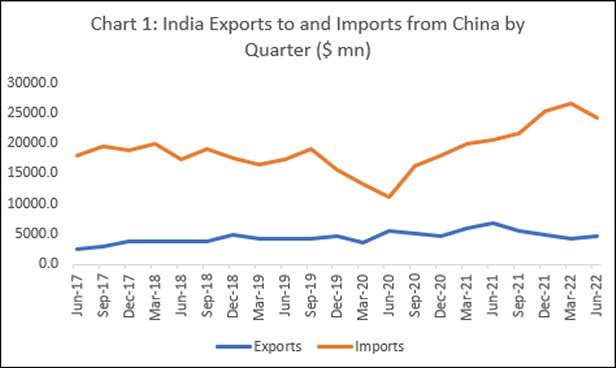

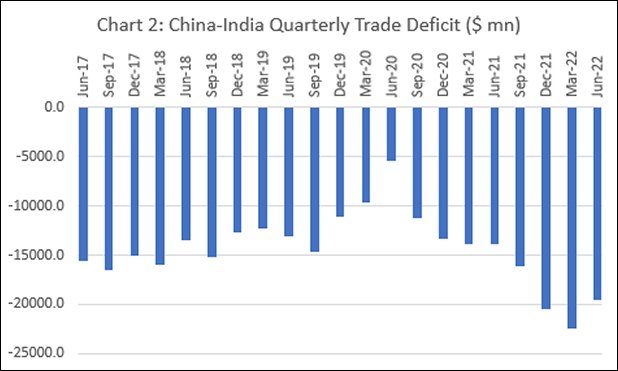

This was no exceptional occurrence. Chart 1, tracing quarterly bilateral trade trends between the two countries, shows that India has continuously run a trade deficit with China over the past five years. That deficit has spiked between quarters ending June 2020 and March 2022 (Chart 2), before recording a marginal decline, possibly because of the supply constraints resulting from the Covid resurgence in China and the Chinese government’s “zero-Covid” lockdown policy. Even so, China alone accounted for more than 15 per cent of India’s imports in 2021-22.

Moreover, more than a quarter of India’s exports to China were primary raw materials such as mineral ores and raw cotton, whereas two-thirds of its imports from China were electrical machinery and equipment, reactors, boilers and machinery and organic chemicals. Such a composition is reminiscent of an era in which underdeveloped countries were exporters of primary products and traditional manufactures, whereas the developed were exporters of more sophisticated manufactures, including machinery.

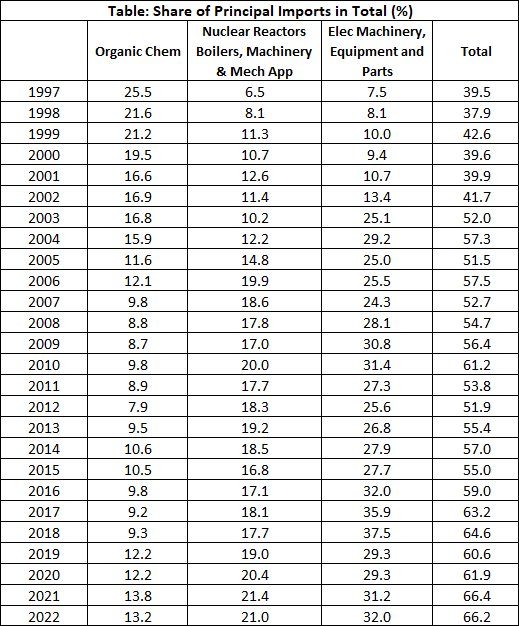

For India, currently hoping to displace China as the world’s manufacturing hub, especially in high technology sectors, this evidence is more than a bit discomfiting. But the cause for concern runs deeper than the economic competition with a neighbour once considered India’s peer. An examination of the composition of India’s imports from China (see Table 1) indicates that since the turn of the century two groups of commodities have dominated: “electrical machinery, equipment and parts” and “nuclear reactors, boilers, machinery and mechanical appliances”.

That is, while India’s exports to China have been dominated by primary products, as noted earlier, its imports have been dominated by equipment and machinery. To recall, in the early years of India’s industrialisation, the strategy adopted as embodied in the Mahalanobis model and plan was to allocate a higher share of investment to the machine tools sector. This was seen as necessary to accelerate growth without running into balance of payments difficulties, because of reliance on imported capital goods and intermediates. What the structure of India’s trade with China, which has emerged as an important trading partner, suggests, is that this strategy was neither successful then (as has been noted by many analysts) but remains unrealised even 65 years after it was first incorporated in the Second Five Year Plan.

Moreover, the presence of electrical equipment in the set of dominant imports from China suggests that even the post-liberalisation goal of attracting foreign investment to undertake production of such products for the world market remains unrealised. Not surprisingly, even the slightest indication that Apple contract manufacturers like Foxconn, Wistron or Pegatron are shifting a small proportion of their production to India because of new difficulties in China is a cause for official celebration.

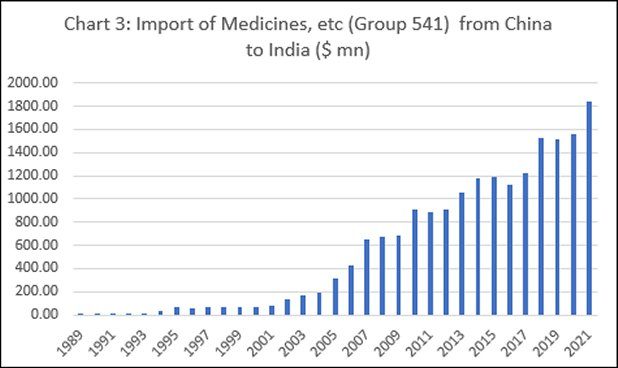

A related feature of the composition of India’s imports from China is the importance of inorganic chemicals, consisting mainly of pharmaceuticals intermediates or active pharmaceutical ingredients. As Chart 3 shows, imports of medicines, etc. (category 541 in the SITC 3rd Rev. classification) have risen rapidly in the years after 2003, when India’s industrial and overall growth accelerated for a period. The result has been a huge increase in the dependence of India’s pharmaceuticals industry on imports of intermediates from China. As a result, any factor, such as the Covid related lockdowns that could adversely affect the supply of those intermediates or their transportation to India, would be damaging for the domestic industry.

This is even more of a damaging indictment of the failure of Indian industrial policy. As is well known, India’s pharmaceutical industry grew rapidly by benefiting from the protection afforded the industry and from the absence of product patent protection (and only process patent recognition). It produced cheap, generic versions of some of the drugs from which transnational firms derived huge profits many years after their first introduction. Moreover, as part of the strategy of building self-reliance in the crucial pharmaceutical sector, the government emphasised production of bulk drugs, including through production in the public sector. That had meant that India was reducing its dependence on imports of bulk drugs as well.

India’s membership of the WTO, its acceptance of the rules governing trade related intellectual property rights (TRIPS) that protected profits of the global pharmaceutical majors), and its reticence under the regime of liberalisation to fully exploit even the opportunities available to favour domestic industry under the terms of TRIPS, eroded all those gains. The evidence on India’s pharmaceuticals trade with China starkly reveals the consequences of that neoliberal policy turn.

Recently, in a much-belated development, the government has been reviving the rhetoric of self-reliance and the need to correct India’s failure to match its one-time peers in manufacturing growth. But a close examination of the policy being adopted using this rhetoric suggests that, while there is some effort to pay off a few favoured domestic business groups and conglomerates by mediating their competition with transnational firms, the government remains wedded to a regime wherein intervention aimed at promoting domestic industry as a sector, based on a ‘nationalist’ industrial policy, is anathema. This can hardly correct this worrisome bilateral trade imbalance.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on November 29, 2022)