Covid Debt and the Tax Paradigm

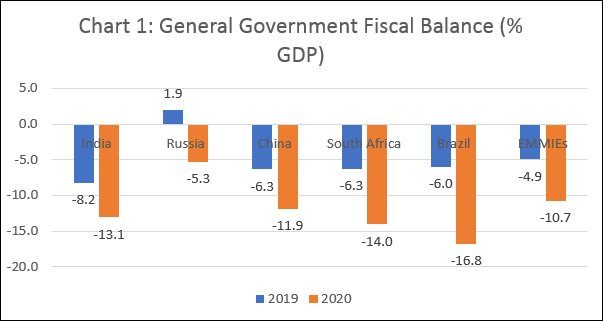

The Covid-19 pandemic has forced governments across the world to increase reliance on debt. The IMF projects the fiscal deficit as a proportion of GDP in emerging markets and middle-income economies (EMMIEs) as a group to rise from 4.9 per cent in 2019 to 10. 7 per cent in 2020 (Chart). That increase is only partly the result of enhanced spending to address the health emergency, compensate individuals and firms for loss of incomes and earnings, and counter the demand compression that keeps production down even after the lifting of lockdowns. A rise in the deficit and the resort to debt to finance it have also been necessitated by the collapse in revenue generation triggered by the pandemic-induced recession.

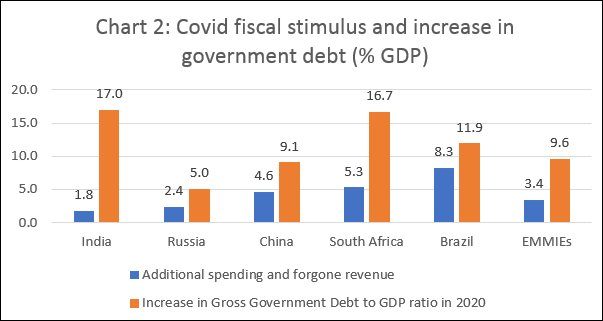

The evidence makes clear that the dependence on borrowing has been larger in countries where the stimulus has been restricted by fiscal conservatism. Larger spending helps raise revenues by allowing for a quicker revival of economic activity, thereby reining in the increase in the fiscal deficit and reducing dependence on debt. Chart 2 tracks the relationship between the size of the fiscal stimulus in some emerging markets and the IMF’s estimates of the likely increase in the fiscal deficit to GDP ratio between 2019 and Covid-year 2020. India, with a low fiscal stimulus (estimated generously by the IMF at 1.8 per cent of GDP), is expected to register an increase in the public debt to GDP ratio of 17 percentage points between 2019 and 2020. That must largely be because of a severe contraction in GDP that also suppresses revenue generation. Emerging markets and middle-income economies as a group, with a fiscal stimulus to GDP ratio of 3.4 per cent (nearly double that of India), are projected to record an increase in the public debt to GDP ratio of just 9.6 percentage points, which is significantly lower than in India. All other countries in the BRICs grouping are expected to do better than India, except perhaps for South Africa with its special problems.

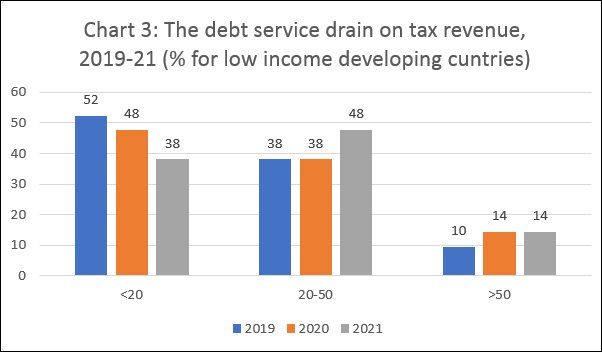

One consequence of the increase in public debt would be that a larger share of future tax revenues would have to be diverted to servicing that debt. The IMF has estimated the likely drain of tax revenues that enhanced borrowing would entail in the case of low-income developing economies. In 2019, 52 per cent of those countries devoted less than 20 per cent of their tax revenues to service debt; that proportion is projected to fall to 48 per cent in 2020 and 38 per cent in 2021 (Chart 3). Instead, the percentage of low income developing countries devoting between 20 and 50 per cent of their tax revenues to service debt is estimated to rise from 38 to 48 per cent between 2019 and 2021, while the share of those allocating more than 50 per cent of tax revenues for the purpose would increase from 10 to 14 per cent. A similar sharp increase in the proportion of EMMIEs suffering a significant drain in tax revenues on account of debt servicing is inevitable.

This problem does not go away even for high spenders, taking into account the superficially “perverse” relation between stimulus spending, the fiscal deficit and public debt. However, the burden would definitely vary with the level of spending. Governments would have been and still would be better off spending more in the midst of the pandemic, not only because of the salutary effect this would have on mitigating the devastating consequences of the virus on health and economic activity, but also because it would make it easier to manage the post-pandemic economy. As and when the pandemic subsides, governments would have to turn their attention to not just accelerating economic revival, but to finding the wherewithal to service the deferred costs of addressing the pandemic, reflected in bloated public debt figures.

Simultaneously addressing these two challenges would require substantially increased resource mobilisation through taxation. But the more damaged an economy is, the more difficult it would be to enhance revenue generation with taxes. Countries that dampened the intensity of the crisis through substantial stimulus spending would then be better off in terms of the extent of contraction that the economy has been through. In addition, these high spenders would have recorded lower erosion of revenues and lower increases in their fiscal deficits and public debt, making the task of post-Covid adjustment that much easier.

Nevertheless, “after Covid”, all countries would, have to substantially enhance revenues mobilised through taxation to service debt and ensure economic recovery, albeit to different degrees. For governments long attuned to the tax forbearance typical of neoliberalism, this would be daunting challenge. More so, because additional resource mobilisation cannot rely on regressive indirect taxes or direct taxes on the lower- and middle-income classes. These are the sections that have been hurt most by the pandemic and its aftermath. Moreover, imposts on these sections would erode incomes devoted primarily to spending (as opposed to saving), compress demand and have low or negative net multiplier effects. Instead, taxes should be levied on wealth and the incomes of the rich and super rich, with any indirect taxation focussing on non-essentials and luxuries. This is bound to trigger a backlash from rich and powerful sections that have had it good for decades now. But if countries have to pull themselves out of the trough they have fallen into, there is no alternative.

There are many lessons that the Corona virus has imparted and many challenges it has posed. Among them is the signal that the era of conservative fiscal policies must come to an end, as must low taxation of wealth and the rich on the specious grounds that this would spur investment and growth . There are signs that some governments have been forced to take heed. But the transformation of the dominant fiscal paradigm has only begun.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on October 20, 2020)