Time use in India

The results of the long-awaited time use survey conducted over January to December 2019 by the NSSO have just been published. This finally allows policy makers and the general public to have some idea of the extent to which unpaid work and other activities determine the lives of people across India.

Of course, there are some concerns with the survey methodology, which must be borne in mind while considering the data. To begin with, the survey was based on the recall method, asking respondents about their activities for the previous 24 hours. Where time use is concerned, this is known to be an inferior and more potentially misleading method, since recall is notoriously inaccurate, and people are often unable to remember and then aggregate the time involved in activities, especially when several activities are combined (as is the case with much home-based work). The use of time use diaries provided to respondents tends to be more accurate, although it is more difficult in social contexts with lower literacy. Direct observation of a researcher could be the best method, but it is not only more expensive and time-consuming, but could be subject to distortion as those surveyed become conscious of the external gaze. Therefore, this was seen by the NSSO as the best available method in the Indian context, given the other constraints. The second concern, however, is also important: for a significant proportion of respondents, this recalled information was not provided directly by the person concerned: for around half the males and one-third of the females, some other household members provided the responses, which could make them even less accurate.

Despite these caveats, the results of this survey are striking, and indicate how enormous the gender disparities in time use are for India as a whole. (Of course, there are also wide regional and state-wise differences, which are not considered here.) The summary results presented by the NSSO refer to all people aged 6 years and above. However, since time use is naturally hugely conditioned by age, it makes sense to exclude children and older people whose time use is likely to be quite different from adults of working age. Therefore, in this analysis we consider only those in the age group 15 to 59 years, for whom the gendered patterns are most likely to be evident.

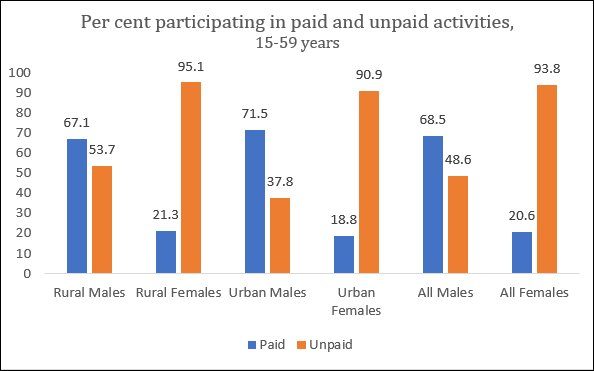

The first immediate result is unwelcome confirmation of the very low paid work participation rates of women. Engagement in paid work among women aged 15-59 years across India came to only 20.6 per cent (Figure 1) and the difference between rural and urban areas has continued to narrow as women’s participation has continued to decline in the rural economy. This compares to paid work participation by nearly 70 per cent of men—already pointing to a significant gender gap in access to monetary income.

Figure 1

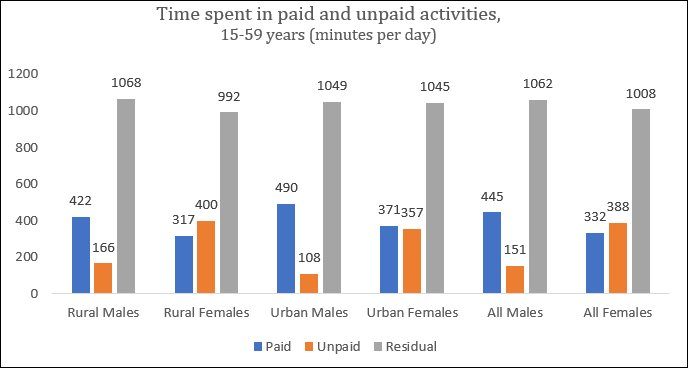

Figure 2

But the much bigger gap is in unpaid work of various kinds. 94 per cent of all women are forced to engage in unpaid activities, mostly involving household work and care of other family members, whereas only around one-fifth of men do so. The time spend in such activities is also much greater for women (Figure 2). On average, women spend more than two and a half times the minutes per day on these unpaid activities than men. In rural areas, women spend nearly six and a half hours every day in unpaid activities, and in urban areas slightly more than six hours. In urban areas, the difference between women’s and men’s unpaid work time is nearly three and a half times.

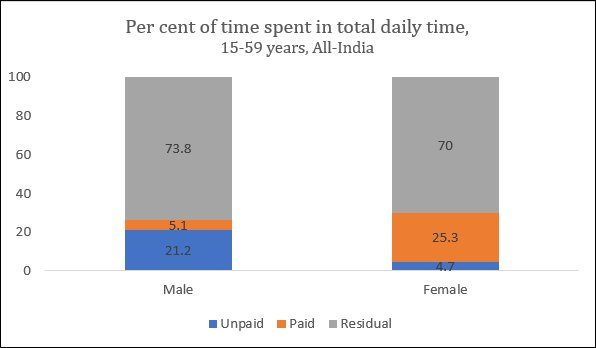

There is a range of “residual activities”, which the NSSO has divided into the following categories: learning or education; socializing and communication, community participation and religious practice; culture, leisure, mass-media and sports practices; and finally self-care and maintenance. It is evident that even for these activities, there is a significant gender gap, with men getting a significantly greater proportion of their daily time to indulge in such activities. As Figure 3 indicates, this is essentially because women are forced to more than a quarter of every 24 hours in unpaid activities, compared to only 5 per cent for men.

Figure 3

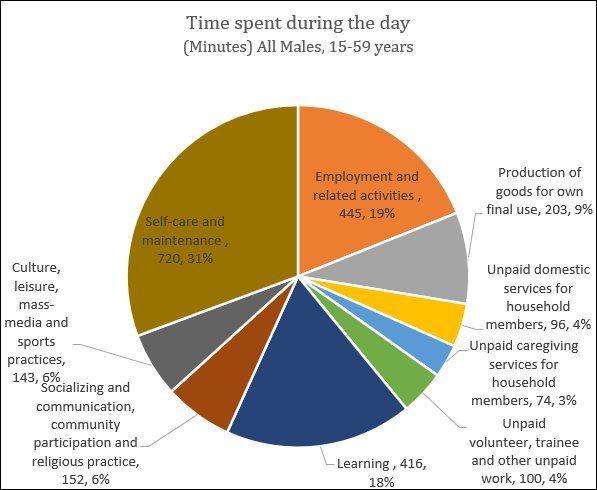

Figure 4a

Figure 4b

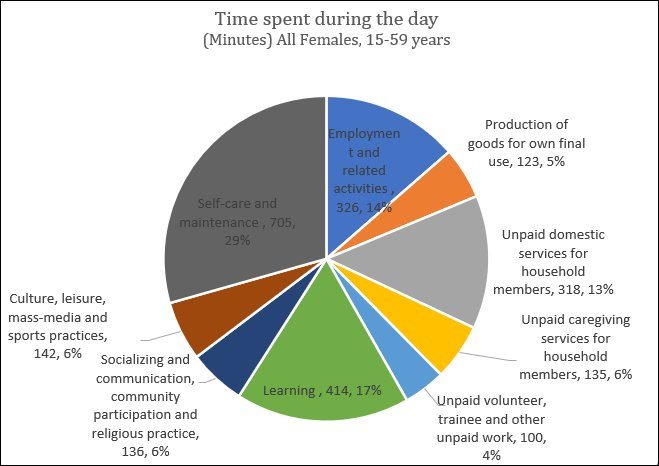

Figures 4a and 4b provides a more detailed breakup of the average time spent by men and women in this age group (15-59 years) including in the various unpaid activities as well as in “residual activities”. It is interesting to see that within unpaid work, men spend 9 per cent of their daily time on production of goods for their own final use, whereas women spend only 5 per cent of their time on this. By contrast, when it comes to working for others in unpaid ways—whether in the form of unpaid domestic services (cooking, cleaning, other processing for domestic use, fetching water and and/or fuelwood, kitchen gardening etc.) or unpaid caregiving services for other household members, men spend only 7 per cent of their daily time on this while women spend 17 per cent, or two-and-a-half times more than men. This is why men also appear to have more time than women for self-care and maintenance, even as the time spent on other residual activities appears to be around the same.

None of this may be so surprising, but it underscores an important aspect of quality of life that is all too often forgotten or ignored by policy makers: that of time poverty. It is evident that there is a very strong gender dimension to time use and time poverty, especially in India where the socio-economic dice are stacked against women in so many ways. Time poverty is more than simply a pressure on time that can create stress and fatigue—it also contributes to material poverty because it reduces the quality of goods and services that are delivered through unpaid activities. It is important for these results of the first official national survey on time use to inform policy making by making more people aware of these issues.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on October 6, 2020)