Finance and the Economy: Fixing the disconnect

India’s stock markets have revived and touched inexplicable peaks even while the real economy braces for what may be the largest contraction in post-Independence economic history. Having collapsed from a level in excess of 40000 in late February, when the Covid-19 pandemic struck, to less than 26000 in late-March, the S&P BSE Sensex has climbed back to well above 38000. Current stock market valuations of most firms can only be justified by expectations of extraordinary increases in sales and profits that, given the context, require not just a “V-shaped recovery” but a subsequent boom in growth. Even the optimists predicting the former are unlikely to place a wager on the latter.

While a disconnect between financial sector and economic performance is by no means unusual, having been observed periodically in the era of liberalized finance, its scale this time and its occurrence in the midst of a deep economic crisis is ominous. A market turn-around and collapse is bound to spill over in myriad ways into other sectors of the economy. It can trigger capital flight and drive down the currency, damaging the balance sheets of firms that have borrowed abroad to benefit from rock-bottom interest rates. It can bankrupt investors who backed their bets with money borrowed from banks already burdened with non-performing assets and further weaken bank balance sheets. There are many such possibilities. A recent meeting of the Monetary Policy Committee of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) recognized these possibilities, noting in its minutes that: “While markets and fundamentals seldom do a tango, a disconnect between the two carry the risks of disruptive market corrections (sic).”

Given these possibilities, intervention to correct for an imbalance that can make an extremely bad economic situation worse, is imperative. Unfortunately, there seems to be little appetite for such intervention. The government is so preoccupied with the mess it has made of its (and the states’) fiscal situation that it has little time to think of reining in the markets, let alone stimulating growth. So, the burden has fallen on the RBI, which thus far seems to have restricted itself to purchasing and accumulating large volumes of foreign currency assets, possibly as insurance against a sudden flight of foreign investors. Foreign currency assets on the books of the central bank rose from $386.1 billion on April 5, 2020 to $492.3 billion on August 7, or by 28 per cent in four months.

Recently, in an interview to a television channel, the Governor of the RBI, Shaktikanta Das, while recognizing the ‘clear disconnect’ between stock markets and the real economy, described it as a global phenomenon and attributed it wholly to the monetary response to the Covid-19 crisis of developed country central banks. That response involved the injection of trillions of dollars of cheap liquidity, some of which found its way to stock markets, including in emerging economies like India. In the Governor’s view, that is what resulted in a stock market revival even when the real economy was steeped in a crisis.

There can be little disagreement with the view that repeated bouts of liquidity injection at near zero interest rates by the US Federal Reserve and other developed country central banks has fueled speculative investments, including in emerging economy stock markets. The question is: what do emerging markets do to mitigate the disruptive effects that such investments can have on their financial sectors and economies? An obvious answer would be that they should adopt measures to prevent the surge in speculative inflows into equity markets in the midst of a severe crisis.

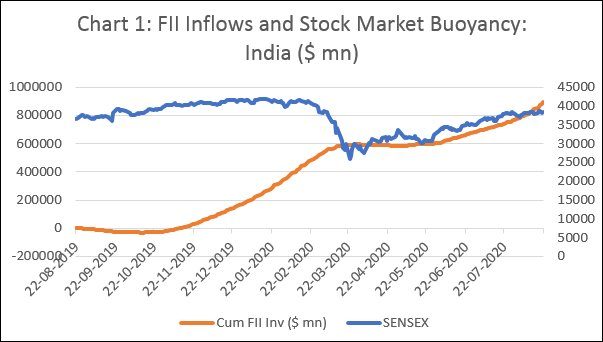

There is reason to believe that this view is particularly relevant for India. Chart 1 tracks the relationship between movements in the Sensex and cumulative net foreign institutional investor (FII) inflows starting from a year ago. Clearly, a rise in the cumulative level of inflows between August 2019 and early-March 2020, kept the Sensex at its record highs, even when the economy was falling into a recession. This changed with the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic and the lockdowns that followed, as net FII investments turned negative and the cumulative level of inflows tapered off. The Sensex quickly lost ground as other market players withdrew in panic. That changed once again, when global financial markets were awash with liquidity. Inflows resumed and soon the decline in the Sensex was stalled, then reversed and a boom followed leading to this phase of the disconnect of stock markets with the real economy.

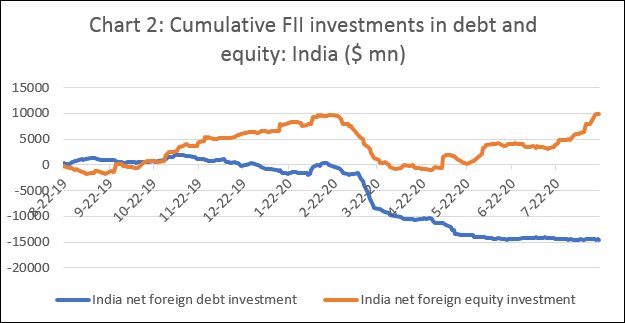

What was noteworthy, however, was this return of ‘investor confidence’ was not visible in the case of FII investments in debt instruments. As Chart 2 shows, there has been a near continuous outflow of FII investment in debt instruments, resulting in a significant increase in the cumulative outflow, whereas cumulative FII investments in equity have tended to be buoyant, except for the brief period between the onset of the pandemic and the launch of the stimulus provided by central banks in the developed countries. Poor economic performance increases the likelihood of default on debt, making debt investments risky even if yields are high. On the other hand, when investments are in equity, especially in shallow markets, based on expectations of a revival, those expectations tend to get realized because of increases in the prices of stocks. Valuations are not warranted by ‘fundamentals’, but that divergence persists till a ‘correction’ or collapse occurs.

In the Indian case, the rise in stocks was also triggered by expectations that the government would work to keep stock markets buoyant. In the midst of a recession, in September 2019, the Finance Minister announced a huge reduction in corporate tax rates, setting off one phase of the recent ‘disconnect’. Promises of more such concessions possibly helped to set off the second phase of the disconnect starting April, when global markets were awash with liquidity. Rather than work to control speculative inflows that lead to a disconnect, policy has encouraged such inflows, driven on the supply side by the injection of liquidity by developed country central banks.

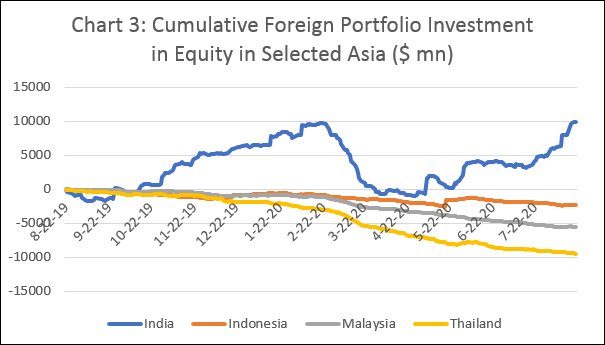

That policy in India mattered is reflected also in a comparison of investment and market performance across selected Asian stock markets. Chart 3 shows the performance of cumulative net foreign portfolio investments in equity in India, Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand. While cumulative flows into Asian emerging markets comparable with India were negative and rising over the year ending August 21, 2020, those into India were positive in much of that period and have recently revived significantly. Clearly, the Indian trend is not evident globally, as the RGI Governor suggested. The policy measures and policy stance of the government have played the differentiating role here.

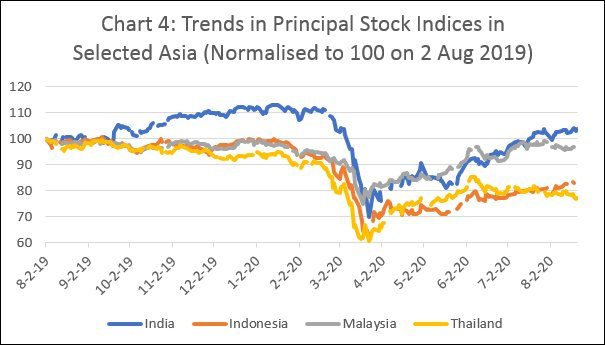

The divergence in cumulative inflow trends has been reflected in stock market performance as well, as Chart 4 shows. India’s market seemed to perform better than the others before the pandemic. When Covid-19 struck, India’s market felt the shock as much as the others. But since then India (along with Malaysia, where domestic investors possibly played a role) has performed better, while markets in Indonesia and Thailand have remained sluggish. Clearly, trends in India are not universal, and cannot be blamed just on external factors. They need addressing. Measures to control speculative inflows are crucial.

Shaktikanta Das predicts that there will be a correction in the future, though he was not willing to commit as to when this would happen. As and when it does, he said, the RBI would intervene to ensure financial stability. But addressing financial market disruption after it occurs is to shut the stable doors after the horses have bolted.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on August 24, 2020)