India’s Foreign Exchange Hoard

For many years now consecutive governments have pointed to India’s comfortable foreign exchange reserves as evidence of the positive effect that economic reform has had on India’s external sector. On June 12, 2015 foreign exchange reserves stood at a comfortable $354.3 billion, or the equivalent of nine months of imports, having risen by $12.7 billion over the preceding two and half months. From a situation of crisis in 1991, when a collapse of India’s foreign currency reserves force it to pledge its gold with the Bank of England to pay for imports, India’s aggregate reserves (in the form of foreign exchange assets, gold and Special Drawing Rights) have ballooned. The confidence this has generated, has given rise to demands for one more experiment with moving to a regime where the rupee is fully convertible.

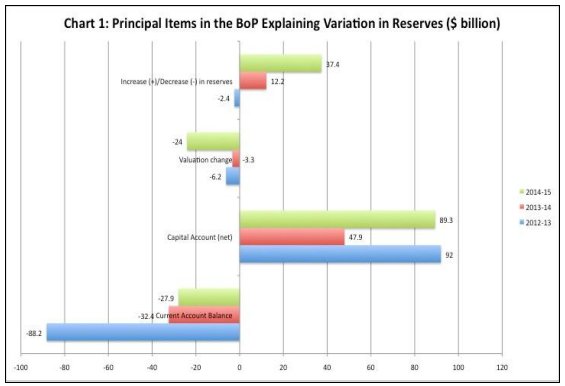

But, an examination of the extent to which and the way in which reserve levels have changed in recent months and years (Chart 1), call for caution. Reserves accumulate when the sum of the current account balance on a country’s balance of payments and the net inflow of capital (after netting out and adjusting for outflows) is positive. The current account balance is, of course, the difference between the foreign exchange that a country ‘earns’ in a particular year and the foreign exchange it ‘spends’ in the same year. Reserves can accumulate if the current account balance is positive (implying a net inflow of foreign exchange) and net inflows on the capital account are zero, positive, or negative to an extent less than the current account surplus. If the current account is in deficit, then the excess foreign exchange spent over the year has to be financed with capital inflows. Reserves accumulate only if net capital inflows exceed the deficit in the current account that needs to be financed.

Seen in this light, a major weakness in India’s balance of payments is that the absolute reserve figures conceal the sources of these reserves. Consider the three-year period 2012-2015, for which the figures from the RBI analyzing the causes for variation in reserves are provided in Chart 1. Reserves are reported to have fallen by $2.4 billion in 2012-13, and have risen by $12.2 billion and $37.4 billion in 2013-14 and 2014-15 respectively. Not surprisingly, the current account deficit that had to be financed by capital inflows was the highest in 2012-13 ($88.2 billion), followed by 2013-14 ($32.4 billion) and 2014-15 ($27.9 billion). But the low level of reserve reduction in 2012-13 and the high level of reserve accumulation in the subsequent two years was on account of net capital flows that were adequate or far in excess of that required to finance the current account deficit. Net capital inflows at $89 billion, were almost as high in 2014-15 as they were in 2012-13 ($92 billion). Net capital inflows exceeded the current account deficit by $3.8 billion in 2012-13, $15.5 billion in 2013-14 and a huge $61.4 billion in 2014-15.

Thus, very clearly, net capital inflows rather than improvements in the current account (which remains in deficit) were responsible for the reserve accumulation. India’s reserves are borrowed in the sense that they reflect inflows that are liabilities to foreign agents, which have future foreign currency payments associated with them in the form of interest and dividend. Not being earned, those reserves can deplete as and when foreign lenders or investors decide to withdraw. This in itself makes the reserve a poor indicator of the strength of India’s external sector.

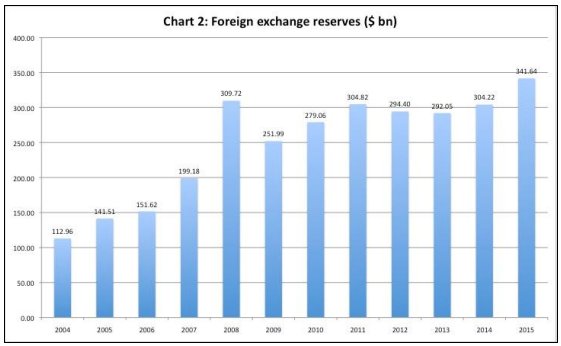

Secondly, as compared to the rapid rise of reserve levels in the years prior to 2004, reserves have not been so buoyant till very recently. It is true that, compared to just $5.8 billion in March 1991, reserves stood at $42.3 billion in March 2001. Subsequently, they rose by 2.7 times to touch $113 billion at the end of March 2004 and a further 2.7 times to reach $309.7 billion in March 2008 (Chart 2). But since, then the absolute level of reserves have been below their March 2008 levels at the end of all financial years, excepting for 2014-15, when they were higher by about $32 billion. While the crisis saw reserves fall steeply in financial year 2008-09, they stood at $314 billion in March 2015. In fact in four out of the seven financial years since 2007-08, the reserve level close at below $300 billion, fluctuating between $252 billion and $294 billion. So the era of rapid reserve increases ended seven years back.

Besides the level of reserves since 2008, an even more disconcerting feature is the volatility in reserve levels since April 2007. Over the year ending 2008, reserves rose by $111 billion or 55 per cent, only to fall by $58 billion or 19 per cent over the next year. Over 2011-2015, reserves fluctuated within a narrow range of $292 billion to $304 billion, falling marginally in two of those years and rising by 9 and 12 per cent in the other two.

Noteworthy are the factors accounting for this volatility. If we return to the analysis of causes for the variation in reserve levels in Chart 1, we find that the differences in volume of reserve accumulation across 2012-13 to 2014-15 were much smaller than warranted by the differences in the excess of capital inflows over the current account deficit. This is especially true of 2014-15, when the excess capital inflow amounted to $61.4 billion but the reserve accumulation was just $37.4 billion. The reason for this difference was what the balance of payments statistics identifies as “valuation changes”. This is the change in the relative values of the currencies and gold in which India holds it reserves. If the dollar appreciates with respect to any of the other currencies or if the price of gold falls in dollar terms, the dollar value of those components of the reserve held in such currencies or in the form of gold will be that much lower. This results in a “loss” or erosion of a part of the benefits of the excess of net capital inflows vis-à-vis the deficit measured in dollar terms. The loss in reserve value due to changes in valuation stood at $24 billion in 2014-15, as compared with just $3.3 billion in 2013-14 and $6.2 billion in 2012-13. Hence, as compared with an excess capital inflow (relative to the current account deficit) of $61.4 billion, the reserve accumulation after discounting for valuation changes was just 37.4 billion. Thus changes in the international value of currencies and gold relative to the dollar, over which India has no control, can make a significant difference to reserve accumulation. That too points to the dangers of relying too much on the absolute dollar value of reserves at a point in time as an indicator of the strength of India’s external position.

(This article was originally published in The Hindu on June 23, 2015.)