The Bogey of Currency Manipulation

In the past decade, talk of “currency manipulation” has become a frequent trope in discussions of international trade. Much of this stems from the US government’s aggressive position on the bilateral trade deficits the US has with several countries, and the associated tendency to blame these deficits on “currency manipulation” by governments of these countries. This has generated a wider tendency for others to assume that some developing countries have been successful exporters by systematically “undervaluing” their currencies.

There are many reasons to question this easy assumption. But whatever little truth there may have been in such an argument in the past, it is really not possible to make the case for this in the current decade since 2010. Consider China, the country against which so much of the Trump administration’s ire is directed. While the ongoing trade war between US and China has many roots (most of all US concerns about China’s growing technological prowess) the persistent trade surplus that China runs with the US has been a nagging sore point.

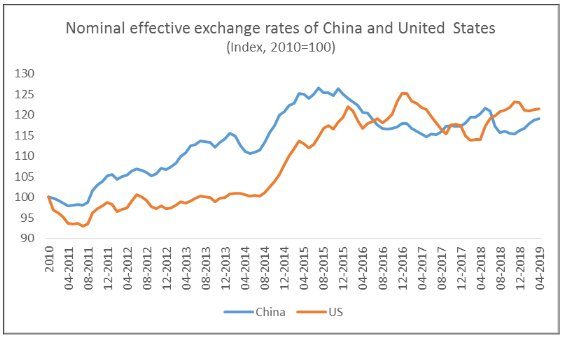

But how much of this has been because of China’s currency being artificially undervalued? Obviously, the correct exchange rate to look at is the nominal effective exchange rate, that is to say the nominal rate (the only one the government or central bank could have even a small ability to influence) relative to the currencies of trading partners weighted according to their shares in trade. Fortunately, the Bank for International Settlements provides data on such nominal rates, as well as real effective exchange rates (deflated by the corresponding consumer prices indices in different countries).

The data in Figure 1-3 are taken from this source (www.bis.org). In these figures, a rise indicates appreciation and decline indicates depreciation, for both nominal and real changes in exchange rates. The data are in index form, with the average of 2010 taken as the base.

This reveals some interesting trends. The first myth that needs to be laid to rest is that of Chinese manipulation to reduce the nominal exchange rate of the RenMinBi. As Figure 1 shows, since 2010, the Chinese RMB (or Yuan) has appreciated just as much as the US dollar, and in some phases the yuan appreciation has been even sharper than that of the dollar. The period of RMB depreciation, between early 2016 and mid-2017, was one of substantial capital outflows from both Chinese companies and rich individuals, and indeed the Chinese state sought to counter this through various measures including those designed to restrict the ability of Chinese firms to invest abroad. Therefore, its actions were actually designed to prop up the RMB, rather than cause it to decline in nominal value – and these measures led to some recovery of the currency. Since then the currency has been volatile in nominal terms, but even so, over the first four months of 2019, the RMB has been 18 per cent higher in nominal trade-weighted terms than its value in 2010 Over the same period, the US dollar appreciated in nominal trade-weighted terms by 21 per cent – hardly a significant difference, and certainly not one that suggests any distinctive behaviour of the Chinese currency.

Figure 1: Since 2010, US dollar and Chinese RMB have both appreciated similarly

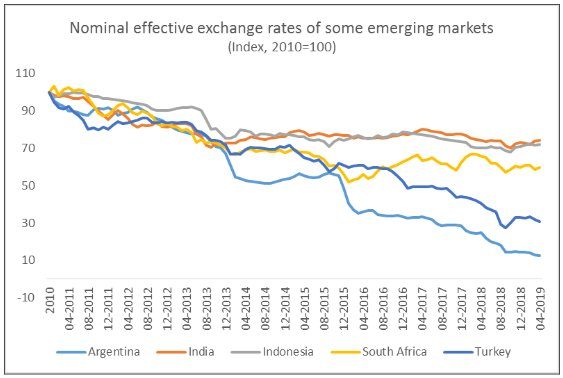

However, there are other currencies of emerging markets that have experienced much more significant declines over this period. Figure 2 indicates the nominal effective exchange rates of some of the worst performing currencies. The most extreme cases are those of Argentina, whose nominal effective exchange rate had collapsed by early 2019 to only 13 per cent of its 2010 value, and Turkey, for which the decline resulted in the lira being worth only 30 per cent of its 2010 nominal value. These precipitous declines were the result of capital flight that in both cases has been prolonged and even accentuated in the recent past. Obviously such disastrous depreciations are the symptoms of extended crises, not of any policy attempt to keep the exchange rates low.

The other emerging markets pictured in Figure 2 that have experienced substantial deterioration in the nominal values of their currencies are India, Indonesia and South Africa. In all three of these cases, the significant depreciations took place in the early years of this decade, and particularly during the period of the “taper tantrum” of 2013. Since 2015 these currencies have been more or less stable in nominal trade-weighted values. Therefore, even though the depreciation with respect to only the US dollar may appear to be more significant for these countries, that reflects the dollar’s appreciation (once again related to the pattern of global capital flows) rather than any actions on the parts of these countries’ governments or central banks. Indeed, if anything, policies in these economies have been oriented towards preventing further depreciation and trying to ensure some stability in nominal exchange rates.

Figure 2: Some emerging markets have experienced major slides in their currencies

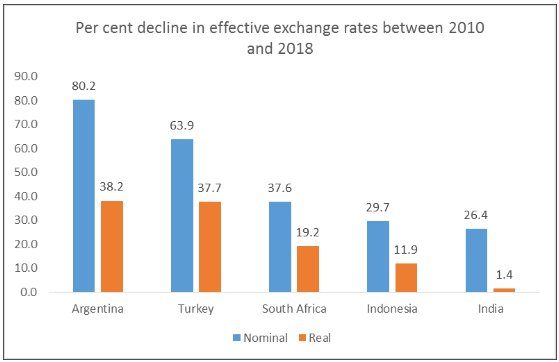

Figure 3: Nominal depreciation does not result in equivalent real depreciation

This is not only because such countries want to avoid being seen as “currency manipulators”. It is really because such attempts to force nominal depreciations make little sense in contexts where these can lead to higher domestic inflation rates. Quite apart from all the other consequences of such inflation, it obviously erodes competitiveness, because the exchange rate that actually matters for trade patterns is the real exchange rate. Figure 3 confirms this point, indicating that the real depreciation in all of these countries has been substantially less than the nominal decline of the exchange rate. Indeed, over these eight years, the sharp nominal declines in exchange rates have been associated with only around half the declines in real terms. In the case of India, a 26 per cent depreciation between 2010 and 2018 has been associated with only around 1 per cent decline in the real exchange rate – in other words, a negligible change that would have no impact on trade competitiveness.

Clearly, therefore, exchange rate manipulation is yet another bogey that has been created to distract attention from the real concerns in international trade. The developing countries that have experienced significant nominal currency declines are more sinned against than sinning.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on June 18, 2019)