Is the Bull Run Over?

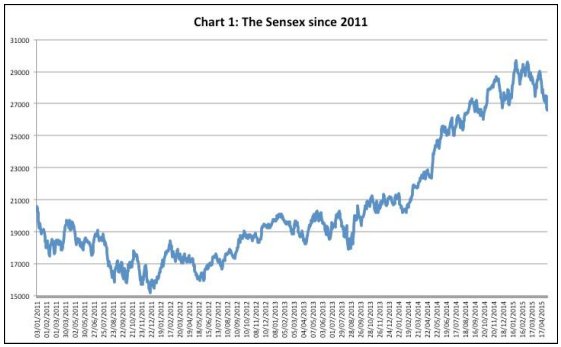

The hurried exit of foreign investors from Indian equity and debt markets seems to be reversing what has been a long bull run in India’s stock markets over the last three years or more (Chart 1). On 7 May, the BSE Sensex closed at 26,599. Though high relative to where the Sensex stood even at the beginning of January 2014 (for example), this multi-day fall of the Sensex troubled investors used to easy profits for many reasons. First, the climb in the Sensex has been so rapid in recent times, that even the relatively high May 7th figure reflected a more than 10 per cent decline from a peak of close to 30,000 realised just three months ago. That would have caught even traders with relatively short trading horizons by surprise. Secondly, there is little disagreement that the bull run, which began three years back when the Sensex was hovering just above 16,000 in May 2012, was driven by the appetite of foreign institutional investors for emerging market taper induced by access to cheap liquidity. So the market analysts who were predicting that the climb of the Sensex will never end because it was driven by India-specific factors, especially the reformist agenda of the new government, were clearly in denial.

Such views have been encouraged by the fact that, in the recent period, even when fears of a change in the investment environment arose, the impact on the market was muted. Thus, in the summer of 2013 when the likely taper of the Fed’s bond purchase policy was first announced, the ‘tantrum’ that followed in the form of FII exit and a market downturn did not last long. Once it was clear that the taper would neither lead to higher interest rates immediately nor squeeze liquidity too much, foreign investors returned and Indian markets resumed their climb. However, those who concluded from these market trends that the boom was robust and resilient were refusing to recognise that both the short term downturn and the subsequent recovery was the result dominantly of the direction of foreign institutional investor movement.

Clearly, what has been happening in Indian financial markets (both equity and debt) is that investors in search of yields have opted for investments in securities that promise quick gains through arbitrage by borrowing at near zero interest rates and investing them in higher-return instruments. This has been encouraged by the high interest rates in India and the fact that capital inflows have kept the rupee strong relative to the dollar, when compared with many other emerging market currencies.

Once that is recognised, the possibility that changes in relative financial returns in India and the US (say) could result in a prolonged period during which investors may (for reasons largely unrelated to domestic compulsions) chose to move investments out of India is real. In fact, if a sufficiently strong exit is triggered, the impact that would have in terms of a market slump and rupee depreciation can aggravate the downturn. It is, therefore, disconcerting that the current slump in the Sensex has also seen the rupee depreciate and breach the Rs. 64-to the dollar ‘psychological benchmark’.

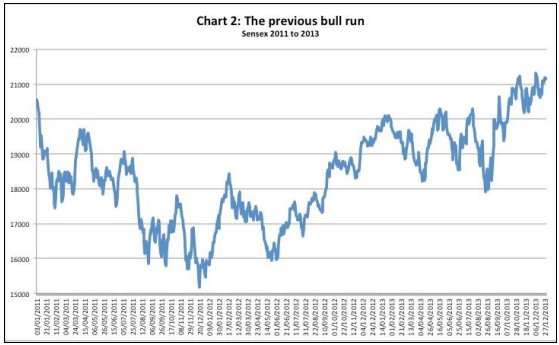

The probability of a sudden reversal that leads to a prolonged downturn is inherent in a market that has seen an unprecedented surge in investment inflows over a relatively long period. Long-term euphoria of that kind inevitably implies that financial investors, blinded by the good times, are not providing for what Hyman Minsky had described as the required “cushions of safety”. In the case of Indian financial markets, the long-term rise in the values of securities can in fact be read as the result of two separate booms spliced together. One ran from 2011 to 2013 (Chart 2), in which the Sensex rose from around 16,000 in May 2012 to a little more than 21,000 by the end of 2013. That was a 30 per cent rise over a year and a half. But this boom was marred by considerable volatility, including the downturn induced by the taper tantrum.

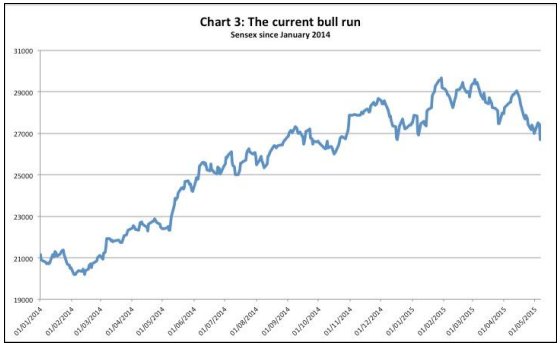

The second boom stretched from the beginning of 2014 till about the beginning of 2015, when the Sensex rose, with far less fluctuation, from just above 20,000 to touch 30,000 about a year later (Chart 3). That was a remarkable rise of close to 50 per cent with a much lower degree of volatility. However, the investor exuberance that delivered this second boom occurred in a period when growth was by all accounts slowing. That meant that such exuberance was in all likelihood irrational. If so, the boom it triggered must end. And when it does, the downturn is likely to be much more severe than witnessed when the taper tantrum based on unfounded fears broke.

The implication of this assessment is not that the current market downturn is definitely the one that would be prolonged and severe. It is only to say that, like earthquakes in seismic zones, such a downturn is inevitable, even though it is impossible to predict when exactly that would occur. The fact, that a host of investors driven by the herd instinct live in denial of this fact only complicates matters and worsens the outcome. Not surprisingly, financial markets are prone to panic, every time when signs of a collapse are sensed.

(This article was originally published in The Hindu on May 8, 2015.)