The Spectre of Higher Oil Prices

On May 2, the Trump administration brought to an end the waiver the US had granted eight countries, including India, of sanctions on imports of oil from Iran. Having pulled out of the 2015 multi-country agreement with Iran to limit its nuclear programme, the US government had invoked the nuclear threat from that country to impose sanctions. The most damaging element of those sanctions for both Iran and the world’s oil importers was the ban this implied on imports of oil from Iran. Even with the waivers, sanctions had significantly reduced global oil supply. According to the International Energy Agency, Iran’s oil exports had fallen to 1.1 million barrels in March 2019 as compared with 2.3 million barrels in June 2018, just after the US sanctions took effect.

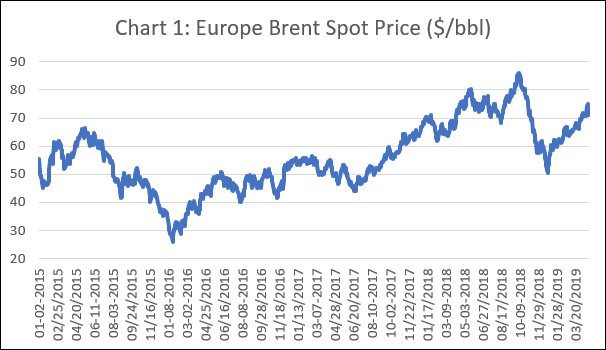

That shortfall worsened an oil supply situation that was already affected by a host of other factors. One was the political standoff in Venezuela, which drastically reduced production in and exports from a major oil exporting nation. The second was a change of mind in “swing producer” Saudi Arabia, which accounts for a third of OPEC production, and had at first refused to cut production when prices started falling in the last quarter of 2014. The price fall was largely the result of over-supply, driven by a boom in shale oil and gas production induced by high prices that rendered US shale competitive. Saudi Arabia’s argument was that if it did cut production and reverse the price decline, shale producers would capture a share in the market at its expense and those of its OPEC partners. But as prices sank to lows that were damaging its finances and affecting its ability to diversify the economy away from excessive dependence on oil revenues, Saudi Arabia decided to join other OPEC nations and enter into an alliance with Russia and 10 other non-OPEC countries to cut production and hold back from the market more than half a million barrels of crude every day. The result was a reversal of the price decline, and in little more than a year the spot price of Brent crude rose from around $45 a barrel to around $85 a barrel. Then, once again prices were on the decline, touching $50 a barrel, only to turn buoyant and touch their recent $70-plus a barrel level (Chart 1). This is the context for the US decision to let the waivers from the sanctions expire.

It is not that the US is not worried about high oil prices, despite the benefits that brings to its own producers, because of the impact it can have on its oil import-dependent allies. But Trump is so hell bent on “punishing” Iran that he has chosen to go ahead, hoping that Saudi Arabia would help by raising production and maintaining supplies at reasonable prices. In one of his now (in)famous tweets he optimistically remarked: “Saudi Arabia and others in OPEC will more than make up the Oil Flow difference in our Full Sanctions on Iranian Oil.” That expectation is based on two assumptions. First, that Saudi Arabia will be willing to go along with Trump’s view that the objective of punishing Iran should be privileged over the unity of a wide range of OPEC and non-OPEC nations it had managed to realise to successfully reverse the oil price decline. Second, that Saudi Arabia’s own interests would not be affected too adversely if prices are allowed to soften.

As noted earlier, the reason why Saudi Arabia agreed to join OPEC in a broad alliance to reduce oil supplies and push prices up significantly, was because the low price regime induced by the shale boom had affected its finances adversely and held back its effort to diversify away from oil dependence. Even with oil prices at $70 a barrel, it is estimated that Saudi Arabia can just about balance its budget, leaving little to finance expansion plans. To finance economic diversification, Saudi Arabia was planning to monetise some of its oil assets through a large offer of equity in oil major Aramco to private investors. That plan, mooted by crown prince Mohammed bin Salman, had to be dropped because of opposition from within the ruling Saudi establishment, which resented the prospect of opening up Aramco’s books to scrutiny for the IPO. In the event, to the extent that Aramco was able to mobilise additional resources, it was through a bond issue. And while bids for the bonds topped $100 billion, the $12 billion worth of bonds that were initially issued soon saw their value fall from their initial issue prices in secondary markets. Keeping investors happy for further rounds of resource mobilisation would require keeping oil prices high and shoring up Aramco’s revenues and profits.

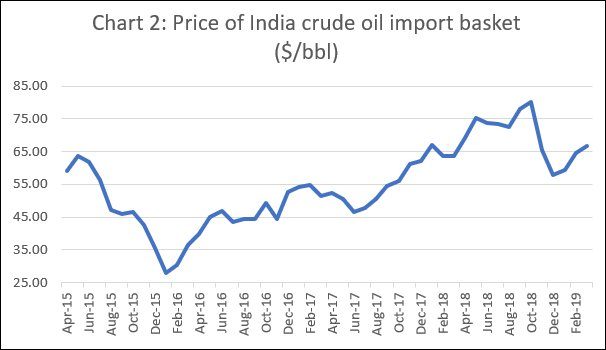

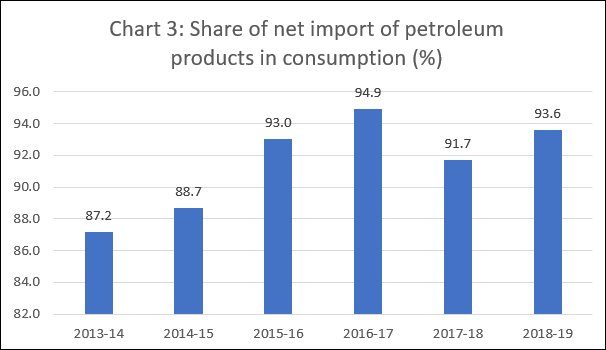

In sum, oil prices are bound to rise in the foreseeable future. That is not likely to be good news for the government that takes control in India at the end of May. The price of India’s crude import basket, which was in decline, has been rising since the end of last year (Chart 2). While consumption of crude and petroleum products in India has been continually rising, touching 212 billion metric tonnes in 2018-19, the share of net imports (after accounting for crude imports that feed exported petroleum products) in consumption has hovered around 93 per cent for the last four years (Chart 3).

So the trade and current account deficits on India’s balance of payments are bound to widen, creating uncertainty among foreign investors even when the political landscape clears. And to that must be added the possibility of inflation, as the effects of higher oil prices (possibly intensified by rupee depreciation) pass through. Oil is a universal intermediate and crude price increases have both direct, second-order and subsequent effects on the price level. That in turn would have its effects on sentiment, interest rates and investment, affecting growth in the final analysis.

So India’s recently strengthened friendship with a Trump-led US has not really helped its economic prospects.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on May 6, 2019.)