The Growing Perils of India’s open Capital Account

In an important new paper (“External balance sheets of emerging economies: low-yielding assets, high-yielding liabilities”, Review of Keynesian Economics, Vol. 9 No. 2, Summer 2021, pp. 232–252) the Turkish economist Yilmaz Akyuz has identified new channels of transmission of global financial shocks resulting from open capital accounts in emerging markets, which have led to “sizeable wealth transfers between emerging and advanced economies. They have also resulted in significant income transfers in view of negative yield differentials between their gross external assets and liabilities.”

In India’s case, Akyuz estimates that between 2000 and 2016, gross foreign assets (claims that Indian residents have on non-residents in foreign currency) increased from 12.2 per cent of GDP to 23.3 per cent, while gross foreign liabilities (claims that foreign residents have on Indian residents in foreign currency) increased much more, more 20.2 per cent to 49.1 per cent of GDP. As a result, the net foreign asset position of India deteriorated from 17.0 per cent of GDP to 25.8 per cent over this period.

It could be argued that this is reflective of India attracting more foreign capital into the country, which would benefit domestic investment. But in the Indian case, we know that investment rates have been falling especially since 2012. Also, Akyuz notes that this is extremely expensive, because the returns on assets have been significantly lower than the returns that foreign residents get on India’s liabilities. Over the period, this loss on account of different rates of return amounted to as much as 5 per cent of 2016 GDP—a really huge and unnecessary loss, that deprives the Indian economy of much-needed resources for its own development.

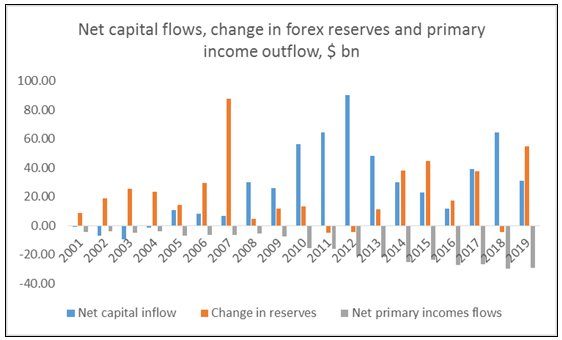

This differential in rates of return is present across many types of international investment and credit. But one major reason for the difference overall is that, even when it seeks to attract foreign investment inflows, the Government of India and the Reserve Bank of India seem unwilling to enable domestic investment to increase commensurately, and instead effectively try to “save” the inflows by adding to foreign exchange reserves. Figure 1 shows how significant the build-up of foreign exchange reserves was in the years leading up to the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, and have once emerged again as significant in the years after 2013. In effect, in recent years the increase in forex reserves has almost counterbalanced the net capital inflows.

This involves three contradictions. First, the capital inflows are not being used to add to domestic investment. Second, the increase in forex reserves that the Indian government proudly sees as an indication of the success of its macroeconomic management, are actually “borrowed”, and do not represent a strength but a rather serious weakness, because they could easily decline rapidly if the net inflows are reversed. Third, the major flaw highlighted by Akyuz is strongly evident in the significant downward movement of “primary income” which dominantly includes investment income, which has been significantly and increasingly negative. This is because forex reserves are typically held in “safe” and low-yielding assets like US Treasury Bills, adding to the difference in rates of return between India’s foreign assets and liabilities.

Figure 1: Net capital inflows have been balanced by increasing forex reserves, leading to falling net investment income

Source for all figures: IMF BPM6 Manual online, 2021

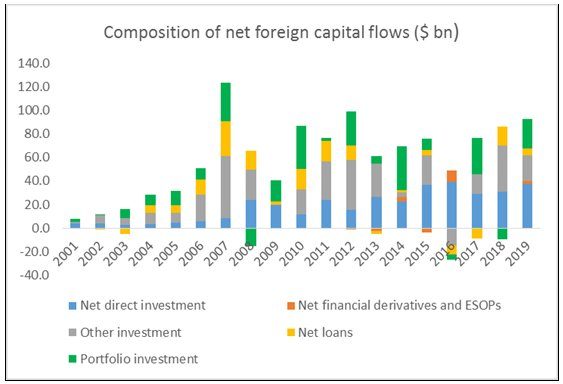

Figure 2: Net portfolio flows have been the most volatile of all capital flows

Figure 2 shows that of the various different types of capital flow, portfolio flows have been the most volatile. However, in recent years, both “other investment” (which includes investment in bond markets) and debt flows have also been very volatile, even turning negative in some years.

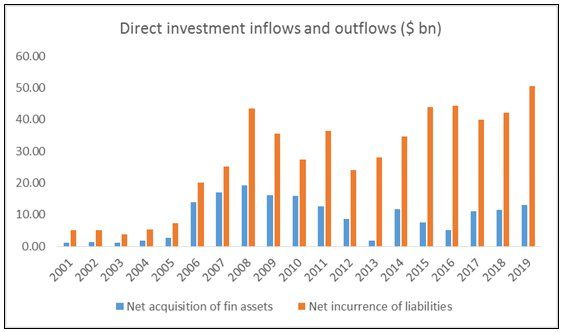

Figure 3: Gross direct investment flows have been much larger than net inflows

Of course, net flows tend to mask the larger gross flows. For example, Figure 2 suggests that net inflows of direct investment have been less volatile. However, this results from the difference between gross inflows and outflows of such investment shown in Figure 3, whereby “net acquisition of assets” constitutes outward direct investment and “net incurrence of liabilities” refers to inward direct investment. It is evident that both of these have been quite volatile, so the net figure provides a misleading picture of greater stability.

If India is not going to “use” the foreign financial flows that enter the country to increase domestic investment, and if allowing such inflows and outflows by residents turns out to be so expensive for the economy, then what is the point of this open capital account? What does it do for the economy other than increase external and financial fragility and cause significant income losses?

These questions have become especially significant during the pandemic, when relatively wild swings in capital flows to emerging markets have already been observed. There is no doubt that the future looks much less promising for emerging market countries in global capital markets, because the massive fiscal expansion in advanced economies like the US and resulting differences in economic recovery and growth will inevitably attract global capital (including from India) to those countries. Matters are likely to be even worse for India because the second wave of the pandemic is not just wreaking havoc upon the population, but damaging any chances of economic revival. The Modi government, whose continued fiscal reticence was hitherto completely unjustified, will soon face real constraints on any future expansionary policies driven by real threat of capital flight.

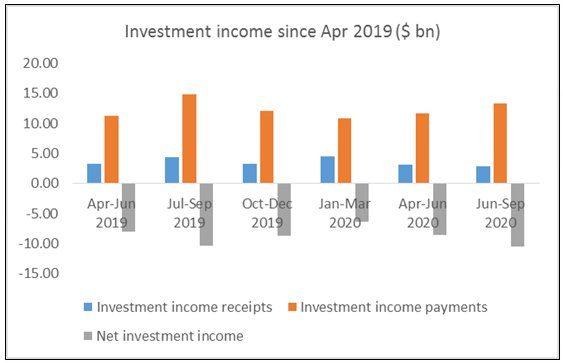

But providing further sops to global capital in such a context will only make things worse, adding to external vulnerability. That is why the decision by the RBI in March 2020, to open up key government bonds to full foreign investment, is both inexplicable and dangerous. It adds to the fiscal constraint that could emanate from volatile capital flows, this time in the sovereign bond market, and to the problems of interest rate differentials that have caused income losses over the past. Indeed, as Figure 4 suggests, in the period since April 2019, and especially since Jan-March 2020, net investment income has deteriorated further in India’s balance of payments.

Source: RBI, India’s invisible payments and receipts, online database.

Unfortunately for the country, the government is handling this economic crisis in exactly the wrong way, in terms of both internal and external economic processes.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on April 19, 2021)