World Economy: The long recession

The world economic outlook released in time for the recently concluded spring meetings of the World Bank and the IMF presents a gloomy picture. Global GDP growth is expected to fall from 3.4 percent in 2022 to 2.8 percent in 2023, and recover only marginally to 3.0 percent in 2024. Advanced economies are expected to experience a more pronounced growth slowdown, from 2.7 percent in 2022 to 1.3 percent in 2023.

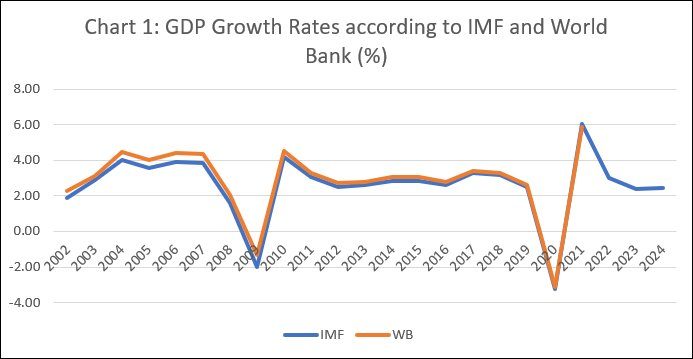

These projections have to be seen in the context of a long and deep recession that has afflicted the global economy since the North Atlantic financial crisis of 2008. According to the IMF there were two years when global economy registered negative growth rates and contracted by 2.02 per cent in 2009 and by 3.22 per cent in 2020 when Covid-19 struck (Chart 1). Despite minor differences, estimates of annual global GDP growth rates from the two Bretton Woods institutions have been in close correspondence. This means the twins share a common understanding on how the world economy has been performing.

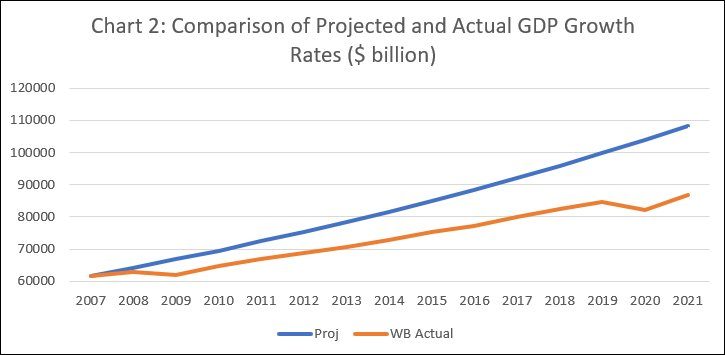

Between these two negative growth years, while there was a return to positive rates, the recovery did not take the world economy back to the trajectory it was on prior to 2008. That hypothetical trajectory can be captured, for example, by computing the trend rate of growth of constant price GDP (in 2015 US dollars) in the World Bank’s World Development indicators over the five year period 2002 to 2007 (4.1 per cent), and using that figure to extrapolate the GDP in 2007 for the years up to 2024. Chart 2 compares the trajectory reflecting these projected GDP numbers and the actual constant price GDP for the world economy available from the World Bank for the years to 2021.

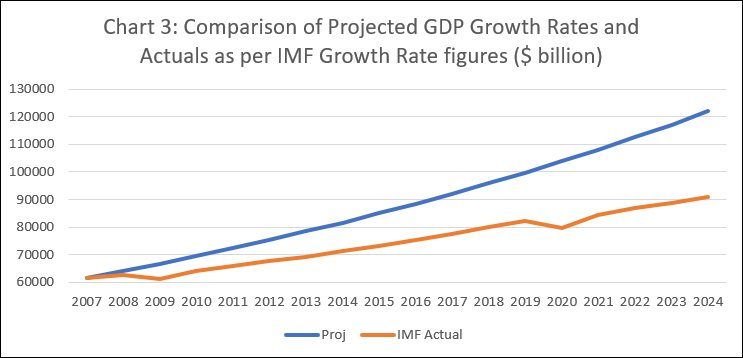

Chart 3 on the other hand compares the projections using the computed trend rate of growth with GDP figures reflecting the annual GDP growth rates for the world economy provided by the IMF, including the IMF’s growth rate projections for 2022 to 2024.

What these charts indicate is that the world economy has slipped onto a low growth trajectory following the Global Financial Crisis. The “actual” trajectory of GDP in both calculations is consistently below the trajectory reflecting the persistence of growth at the 2002-2007 trend rate. Moreover, the gap between the two trajectories – projected and actual — has widened in both sets of comparisons. In fact, if the IMF’s most recent projections for growth in 2023 and 2024 hold, the divergence between projected and actual trajectories would increase.

In recent times, the seriousness of this long-term growth crisis has been underestimated by attributing it to external or exogenous factors and/or shocks. First, slow growth was blamed on the uneven recovery from the Great Recession across countries and continents. Then, slow growth was attributed to the impact of the Covid pandemic and the sudden and repeated stops to economic activity it resulted in. Recovery from that downturn was seen as having been weakened by the inflation that followed the onset of War in Ukraine, which forced advanced economy central banks to raise interest rates rather quickly with adverse effects on consumption and investment expenditures. And now, the expected slowdown is being attributed to the banking stress that has resulted from the hike in interest rates.

This tendency to treat the long-term slowdown as consisting of a series of short term events and attribute each of them to specific, transient causes is not without intent. It helps divert attention from the fundamentals that underlie the long-term slowdown. The pre-2007 growth trend, which provides the benchmark for our analysis of the slowdown, it is widely acknowledged, rose on a credit bubble, which was confined not just to the housing sector. It was the unwinding of that unsustainable, credit-fuelled spiral that triggered the financial crisis and the Great Recession. In the absence of a similar bubble, capitalism seems to have lost the dynamism it displayed in the two decades following the end of the Second World War.

And with a distaste for fiscal activism, aggravated by the fear of inflation, characterising macroeconomic policy, governments in the advanced countries have lost any ability to pull their economies out of the depressed growth the system seems trapped in. Cycles resulting from factors like the Covid pandemic are superimposed on this low growth trajectory, worsening each such downturn. While transient reliance on fiscal stimuli helped some countries like the US to pull themselves out of the deep troughs into which they had fallen, monetary policy instruments have become the staples for macroeconomic management. The severe crisis in banking and the real economy led to exceptional or “unconventional” monetary policies involving quantitative easing or the infusion of large volumes of liquidity into the system as well as near zero interest rates.

This was in essence an effort to set off another round of credit-fuelled growth. But the evidence shows is that it did not work. While the abundance of cheap liquidity helped banks stave off insolvency and triggered speculative investments in financial assets that set off a boom in stock and bond markets, it did not revive the real economy. Households burdened with debt accumulated in the run up to crisis were clearly unable to obtain more credit or unwilling to increase their indebtedness. In the event, the recovery was weak and growth stayed well below pre-2008 levels.

When the pandemic struck, the resulting economic contraction occurred in this context of slow growth. The economic setback was therefore severe. Fiscal stimuli were initially resorted to, in an effort to pull economies out of the depths of the crisis. But in time the main instruments relied upon were monetary, which limited the recovery. More recently, to the surprise of policymakers in the advanced nations, inflation that emerged as the pandemic waned and was attributed to the clogged supply chains, has persisted. Speculation-induced price increases that followed the invasion of Ukraine only aggravated the situation. Responding in panic to persistent inflation, central bankers hiked interest rates repeatedly. Banks that had diverted some of the surplus liquidity accumulated during their quantitative easing years to bonds that seemed riskless, found the value of those assets falling inflicting real or notional losses. Stress because of such factors associated with the interest rate hikes, is seen as limiting credit flow and affecting investment and consumption demand. But lowering interest rates again is not seen as an option because of the fear of fuelling further inflation. Policymakers in the advanced nations have lost the only means they think they have to address the next crisis.

The problem of tepid growth in the long run is now being transformed into one of stagflation reminiscent of the decades that followed the end of the Golden Age of capitalism in the 1970s.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on April 17, 2023)