National Income during the Pandemic

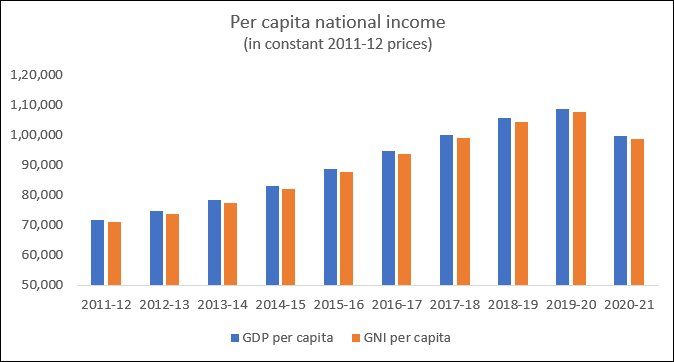

It is obvious that the Covid-19 pandemic has had a deep, searing impact on the Indian economy, in terms of both total economic activity and livelihoods. It is true that the economy had been struggling for several years before then, with falling investment and employment, sharply growing inequalities and worsening conditions of health and nutrition. But the pandemic and the policy response led to sharp aggravation of all of these problems. As Figure 1 show, per capita income in real terms, whether measured as GDP per person or as net national income per person (which is GDP after subtracting taxes and adding subsidies) fell by nearly 9 per cent in 2020-21 compared to the previous year. Indeed, per capita income in 2020-21 was lower than even four years earlier, and just barely above the level of five years before, undermining the growth of the intervening period.

Meanwhile, since we know that India also had some of the most rapid increases in income inequality anywhere in the world, even this declining income was much more unequally distributed. This meant significant worsening of the material conditions of the bulk of the population, with the bottom half of the population (around 650 million people) probably being the worst affected on the planet in terms of deteriorating economic circumstances.

Figure 1

In official circles, much as been made of the economic recovery since then. It has been argued that the pandemic year, and especially the period of the national lockdown, was especially hard, but thereafter the economy has supposedly “bounced back”. The government’s “Economic Survey” for 2021-22 claims that the Indian economy has already grown beyond pre-pandemic levels and “is well placed to take on the challenges of 2022-23.” (page 3) So it is worth examining recent trends in output, as described in the official National Accounts Statistics quarterly estimates.

One important caveat: The advance estimates are very much “guesstimates” and tend to be revised over time, with first and second revisions often showing quite significant variation from the advance estimates. Quite often in the recent past, the revision has been downward: for example, the annual decline in GDP in April-June 2020 was estimated to be 23.9 per cent in the advance estimates, but has now been revised downwards to 24.4 per cent. So the most recent data provided by the CSO, and its advance estimates for 2021-22 that have been used in Budget-2022-23, need to be treated with appropriate caution. Note that this is quite apart from all the other concerns with the CSO’s new method of estimating GDP that have been widely commented upon.

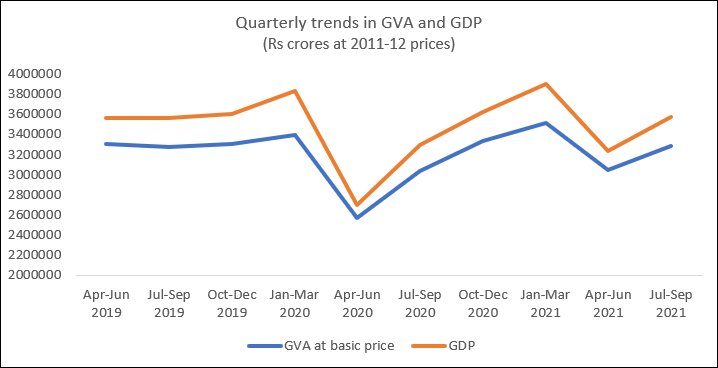

Figure 2

Figure 2 suggests that while there was indeed a recovery of both GDP at market prices and Gross Value Added at basic prices from the trough of April-June 2020 to January-March 2021, this was followed by subsequent decline. In July-September 2021, GDP was still 7 per cent below the level of January-March 2020, the last pre-pandemic quarter. Some of the decline in April-June 2021 can be attributed to the impact of the disastrous second wave of the pandemic that proved to be more lethal in India than the first wave. But there are other, deeper problems with the so-called recovery that cannot be ignored.

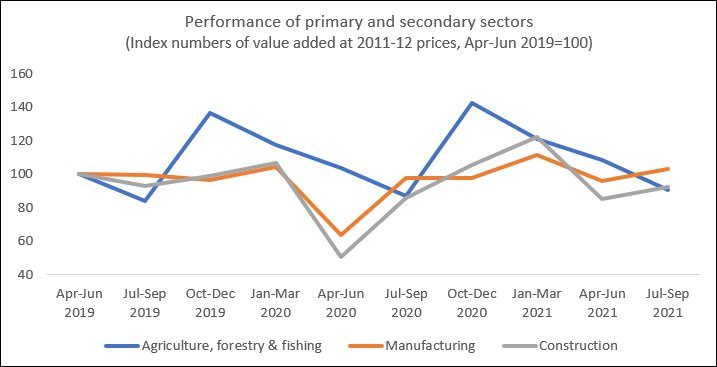

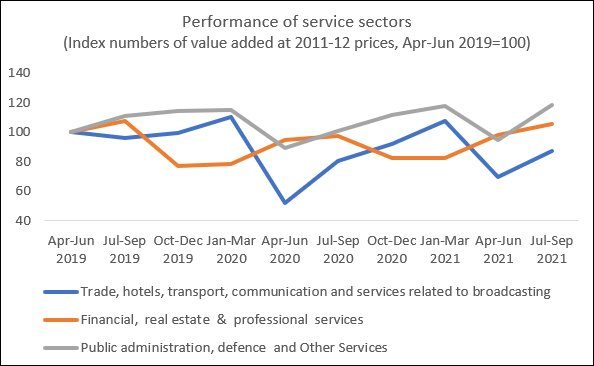

This becomes more apparent when a sectoral breakdown of the GDP trends is examined. Figure 3 provides data on quarterly output of the so-called “material producing sectors”: agriculture, industry and services. In Figure 4, data on the services sector are shown. The two taken together are both instructive and alarming.

Agriculture was the sector that provided the only ray of hope for the Indian economy in 2020-21, as a good monsoon enabled agricultural output to rise dramatically even as other sectors were in decline. But thereafter, the value added in agriculture has been declining continuously. In July-December 2021, agricultural value added was 34 per cent lower than the peak of October-December 2020, 23 per cent lower than January-March 2020, and even lower (by 9 per cent) than the level in April-June 2019.

Figure 3

Figure 4

Similarly, manufacturing was supposed to have swung back into higher activity. But despite a temporary jump in January-March 2021, by July-September 2021 the sector’s value added was still lower than in the pre-pandemic quarter January-March 2020. Even construction, which showed a big jump in January-March 2021, fell thereafter, so that by July-September it was 13 per cent lower than the level reached just before the pandemic.

The services sector on the whole appears to have performed slightly better, but here too the “recovery” has been extremely uneven at best. The only consistent increases after the lockdown slump have been in public administration, defence and other services—largely as state governments stepped up their spending to deal at least partially with the massive humanitarian crisis that was unfolding. But trade, transport communication and other services that are closely related to material economic activity did not recover in the same way: in July-September 2021 the value added was 21 per cent lower than in the pre-pandemic quarter. However, most recently finance, real estate and professional services have shown a recovery, which may not be a cause for celebration if it indicates a speculative bubble unmoored to the real economy.

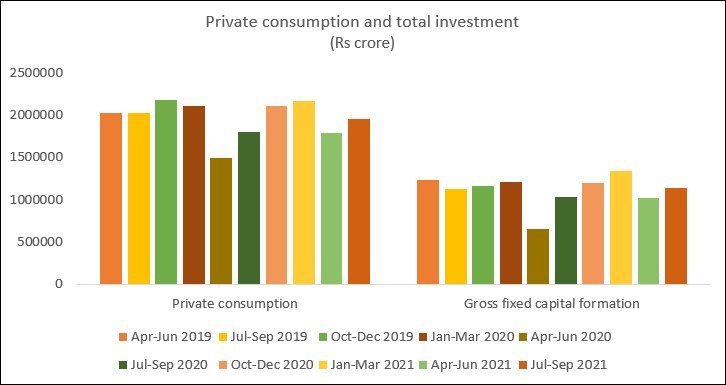

Figure 5

The performance of particular sectors is the counterpart of trends in consumption and investment. In this regard, the data in Figure 5 are telling. Private consumption, which was already sluggish before the pandemic, collapsed in April-June 2020 and then showed very uncertain recovery. In July-September 2021, it still remained 7.5 per cent below the pre-pandemic level, suggesting a real curtailment of domestic effective demand. In such a context, it is not surprising that investment also has not really recovered. In the most recent quarter, investment was still 5 per cent below the pre-pandemic level.

These trends do not suggest a robust economic recovery. The basic macroeconomic problem remains the same: a contraction of domestic demand because of falling employment, wages and incomes of self-employed, as the informal economy and small and micro enterprises continue to bear the brunt of the economic difficulties. The growing inequalities can create more consumption by the super-rich, but that will not be enough to dig the economy out of its current hole. A government in denial of this obvious fact can only make things worse.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on February 21, 2022)