The Battle to Defend the Employment Guarantee Scheme!

As I write, roughly 10.3 million workers return home as the sun sets on 4.9 lakh worksites across the length and breadth of this vast country under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme. About 23% are Scheduled Castes, and 17% are Scheduled Tribes. With a failed monsoon and drought behind them, and fall in the growth rate of real wages, such employment and wages could offer the much needed succour from the consequent misery and even reduce distress out-migration. With luck, the next failure of the monsoon could then not be as bad in impact, as the assets created under the scheme would add irrigation facilities and hold soil-moisture. Or they could generate other means of livelihood. The women who account for more than half the workers under the scheme may still get no rest as they rush to light their kitchen fires and do domestic chores to end the day of back-breaking work, but they could have the satisfaction that no one will sleep hungry.

I use “could” instead of “would” because the reality is that successive governments have neither provided the promised days of employment, wages or timely payment, breaking the sacred promise made to the working poor of rural India.

Potential to address rural distress

MGNREGS is unique in many ways. Contrary to the unfounded claims by detractors, it is neither “wasteful” nor “ineffective”. It provides 40-50 days of annual employment to a fourth of rural households, no mean achievement in itself. At its peak, it increased rural wages, thereby reversing a six-year period of stagnation in rural wages – and reduced the gender gap in wages. The provision of work within five kilometres of residence, equal wages for men and women, and even the minimal worksite facilities like care of children of workers, etc., improved gender parity and female work participation rates.

AIDWA’S studies in the early years across 8 states demonstrated that the legislation reduced distress migration from endemic areas, cleared debts and reduced indebtedness, increased household expenditures. It supported eco-regeneration and asset creation in many places. According to Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research’s recent field study in Maharashtra, MGNREGS workers have “replaced scrublands with forests, built earthen structures for impounding water and preventing soil erosion, cleared lands and leveled them to make them cultivable”, This is scarcely “digging pits”. Another study by Institute for Human Development in Jharkhand found that MGNREGA wells have a real rate of return of 6 per cent (more than most industries). A recent panel survey by the NCAER shows that it has reduced poverty among STs and SCs by 28 and 38 per cent, respectively. Indeed, it was credited as the hero in India’s ability to not go down during the world economic recession.

Strong Opposition

The Act is also unparalleled in the strong resistance and hysteria it elicits from the urban elite, the corporate sector, the rural elite, and the media. The opposition by the landlords and rich peasants who squeeze profits from exploitation of the rural workers don’t like the Scheme as it increases the bargaining power of workers. The fall in the viability of agriculture on account of rising cost of non-labour inputs due to neo-liberal policies without effective public procurement at remunerative prices has added to their opposition. Right wing economists, who seem to have no problem with corruption in large projects and contracts of various kinds, constantly harp on corruption in MGNREGS, as if it doesn’t exist elsewhere. The groundswell of favourable opinion from rural workers, social activists and the Left’s strong Parliamentary presence held the day, ensuring crucial amendments to improve the UPA’s rather insipid original proposal.

Ten years ago, when the Bill was passed unanimously by Parliament, the BJP proposed very radical amendments to increase the entitlements for rural workers. Forgetting this, PM Modi on 28th February 2015 disparagingly declared the employment guarantee scheme to be an epitome of six decades of failure of the Congress party. The NDA is clearly not a friend of the Scheme and attempted several dilutions as soon as it took office – restricting it to the poorest districts, reducing the wage component, introducing greater rigidity in the type of works that could be taken up. So what is surprising is the PM’s complete U-turn, on the scheme’s tenth anniversary, when he hailed MGNREGA’s achievements as “a cause of national pride and celebration”.

Almost as ridiculous is the erstwhile Congress PM and FM’s rather childish squabble for ownership of a Scheme they themselves did not want. Quick to point out PM Modi’s flip flop, they conveniently forgot their own concerted attempts to first thwart then restrict and finally starve the Scheme. The UPA government even challenged the Karnataka High Court’s order that Government pay statutory minimum wages and arrears to workers in the Supreme Court (where All India Kisan Sabha was the respondent).

The Act is supposed to be demand-driven, and in the face of demand (up to the specified limit of 100 days per rural household) funds must be transferred to states. So to cap central government allocations is illegal, but such is the arrogance of the centre that the Chief Minister of Tripura, the best performing state, had to sit on a dharna at Jantar Mantar in New Delhi, demanding that funds be released. Through its history, the government of the day has starved it of funds, delayed wage payments, underpaid workers, and not generated promised employment.

Sabotage from within

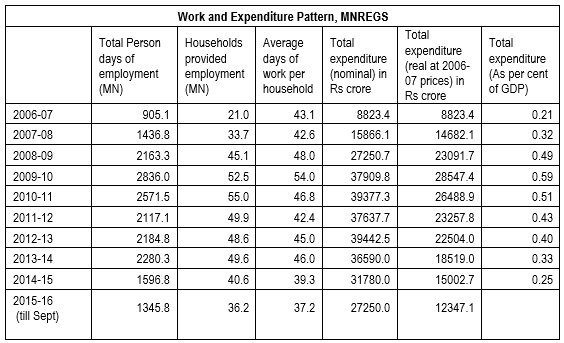

Even a cursory analysis shows that people’s entitlements guaranteed under the law have been systemically undermined by both UPA and NDA. First the UPA Finance Minister repeatedly cut outlays and now the NDA Finance Minister has made outlays conditional upon tax revenues rising (and even then not lived up to his promises). This dreadful disrespect for the law has kept allocations and spending low. Total expenditure in nominal terms grew from Rs 8823 crores in the early years as it was extended from 200 districts to the entire country, peaking at Rs 39442 crores in 2010-11, after which it fell even in nominal terms (from the last years of UPA 2). Allocations have not kept pace with inflation and GDP growth, falling both in real terms and as a share of GDP. In real terms, it is currently almost half of its peak level. As a share of GDP, it has never exceeded 0.6%, falling steadily after 2009-10.

This has meant that state governments are starved of funds to keep the programme going. At present around 14 states are reporting a negative balance, which means that they have to divert money from other uses and also keep workers unpaid for work already done, sometimes for many months.

Source: Jayati Ghosh (2016) MNREGA under the Modi regime

This has had a highly negative impact on the reliability and usefulness of the programme in stemming rural distress and poverty. At its highest, the total number of households that were provided any employment was 55 million, and the persondays of employment generated were 2.8 billion, never exceeding 54 days per household per year, a far cry from the promised 100. The total number of households that completed 100 days of wage employment is 22 lakhs so far in this fiscal year, comparable to 24.9 lakhs last year. This is less than half in the previous two years (46.6 lakhs and 59.3 lakhs respectively). Only 69% of the approved labour budget has been met this fiscal, compared to 75% last year.

The failure to provide adequate and timely funds, rigidity in permissible works and inadequacy of personnel has made things worse. Despite lip service, the approach to project planning is top-down and except in a few pockets, social audit and grievance redressal remain mere promises. Social audit provided in the Act to ensure accountability and transparency has been done only in 25% of the 662 districts this year.

Lack of political will is reflected in the abandonment of the Scheme’s commitment to the timely payment of minimum wages. Wage payments are severely delayed with Rs 4500 crores unpaid in FY 2013-14 and about Rs 6000 crores in FY 2014-15. More than Rs 11,000 crore worth of wages have been pending for over 15 days in the current financial year, and last year over 73 per cent wage payments were delayed. The hype over jan dhan bank accounts notwithstanding, the percentage of payments generated within 15 days is only 43.34, compared to an even poorer 26.85 last fiscal.

India has recently faced bad monsoons and drought, and there has been a fall in the growth of real rural wages. This has once again exacerbated agrarian distress. And yet, shamefully, despite reminders from the Ministry of Rural Development, funds were not released to meet its own commitment of 150 in the six drought affected states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Telengana and Uttar Pradesh. The Finance Minister, who had promise an additional Rs 5000 crores for the scheme (as if it is a “gift” from the Finance Ministry rather than a legal obligation) has recently provided only Rs 2,000 crore more, disregarding his own promise and in blatant violation of the law.

Struggle ahead!

Ensuring the proper implementation of MGNREGA is therefore a struggle, one which has to be constantly fought. The opposition comes from capitalists in search of cheap and “flexible” labour, who feed off poverty and distress. It comes from finance capital, who want low fiscal deficits accompanied by huge tax concessions, which for them requires cutting subsidies public expenditure on employment, social development, etc. It comes from the land sharks preying on the impoverished peasantry to grab their natural resources. Just as the Left forced the UPA government to pass an improved Act, it has to organize MGNREGA workers to fight for their rights. The right to work has to become the sustainable foundation for broad based and labour intensive alternative development strategy. This is why vested interests oppose MGNREGA, and that is precisely why we must defend it.