Banking on FDI

Recognising the well-known fact that in terms of industrial growth India has fallen behind many of its former peers such as Brazil and South Korea, the NDA government has made the revival of manufacturing the centre piece of its economic strategy. However, the policy to be adopted to realise this objective has been reduced to the “Make in India” slogan, often preceded by the word “come”, suggesting that the intention is to attract foreign investors to invest in manufacturing in this country to produce for export to markets abroad. The government’s role, if successful, would be to fashion the policy environment and ensure the infrastructural conditions needed to facilitate such investment.

This strategy is by no means novel, having been experimented with by many a developing country in the past four decades. Other than a few, most such experiments have failed. And making this bet at a time when the world economy is still battling with recession may not be all too wise. What is more, given India’s large domestic market, even when foreign investors come to India they are likely to make for the domestic rather than the export market.

Consider for example India’s own past experience. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has recently released a bunch of numbers on the foreign assets and liabilities of companies registered in India and the finances of Foreign Direct Investment Companies (FDICs) operating in India. (FDICs are firms in which a single foreign investor has at least 10 per cent of equity, which (arbitrarily) is taken as indicative of substantial and long-term interest.)

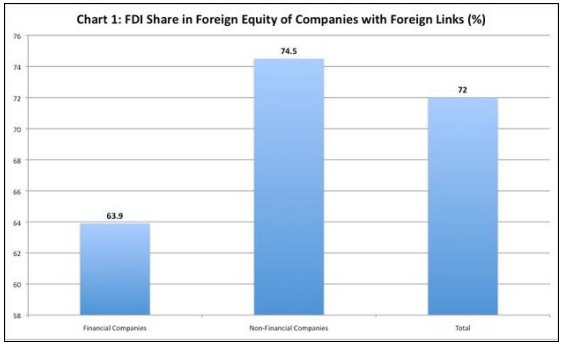

Since 2011 the Reserve Bank of India requires all companies that have received foreign direct investment and/or themselves made investments abroad to file returns on their foreign liabilities and assets. This information collated and released by the RBI point to significant domination by foreign firms in the foreign invested sector. Thus the share of FDI in equity (at market value) of companies with foreign ownership of equity stands at 63.9 per cent in the case of financial companies, and a larger 74.5 per cent in the case of non-financial companies (Chart 1).

Further, the market value of the stock of foreign direct investment equity at the end of March 2013 amounted to 59.4 per cent of the total value of invested capital minus outstanding loans in the registered manufacturing sector. This overwhelming presence, no doubt, partly reflects the unwarranted asset price inflation in India’s stock markets. But, it must be remembered that foreign investors not only own equity of this value. As a result of holding that equity as the largest or the majority shareholders in various enterprises, they have management control of all assets in those enterprises.

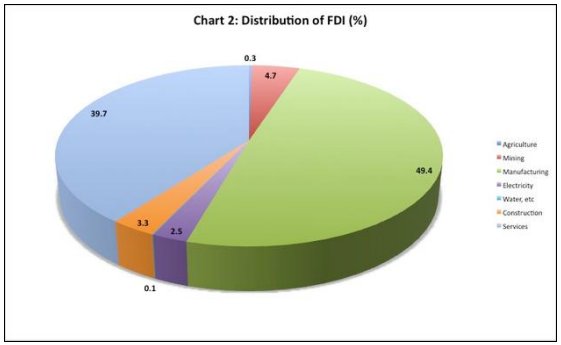

Thus, as the Indian government stretches itself to attract more foreign firms to come make in India and convert the country into another manufacturing hub for the world, it may be useful to assess some features of the experience with these firms that are already making in India. There are clearly two sectors into which foreign capital dominantly flows: manufacturing (which accounts for close to 50 per cent of FDI equity valued at market prices; and services (especially financial and business services) which accounts for another 40 per cent (Chart 2). So firms do clearly come into the sectors in which the government sees India as having an advantage because of a low wage, skilled and partly English-speaking workforce.

What is striking is that despite the claim that liberalisation, by exposing domestic capacities and firms to the cutting edge of international competition, would restructure and render them internationally competitive, subsidiaries of foreign manufacturing firms in India are not using India as an export platform. Taking foreign subsidiary companies as a whole exports accounted for a reasonable 32 per cent of their sales. But that was because firms in the ‘information and communications sector’, which accounted for 17 per cent of sales of all firms covered, exported as much as 70 per cent of their sales. Foreign firms that were investing in manufacturing in India, on the other hand, were largely catering to the domestic market. This has had a curious result from the point of view of the balance of payments.

Data on the finances of 917 non-government, non-financial foreign direct investment companies in 2012-13 released early January show that over the three-year period 2010-11 to 2012-13, the earning in foreign currencies of foreign direct investment companies averaged 22 per cent, whereas that ratio in the case of non-FDI companies stood at a higher 26 per cent. Foreign invested firms were less engaged with export markets when compared with non-FDI firms. Evidence from the past suggests that the net foreign exchange earnings of FDICs is negative.

Hence, unless the policies adopted by the government result in a fundamental transformation in the behaviour of foreign firms investing in Indian manufacturing, the hope that the country could ride on their backs to export-driven economic success is likely to be belied. That would be true even if the world economy recovers from the current recession.

*This article was originally published in The Hindu on February 4, 2015.