India’s Remittance Lifeline

With the deficit on India’s trade in goods and services widening, from $19 billion in the quarter ending September 2021 to $49 billion in the corresponding quarter of 2022, net inward transfers recorded in the current account have become crucial to rein in the current account deficit. Personal income transfers provided India with a buffer of $25 billion during July-September 2022, of which $16 billion were on account of worker remittances, according to figures from the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). India is the world’s largest recipient of remittances (far ahead of second-placed Mexico), according to the World Bank’s Migration and Development Brief of November 2022, with flows projected to exceed $100 billion for the first time in 2022.

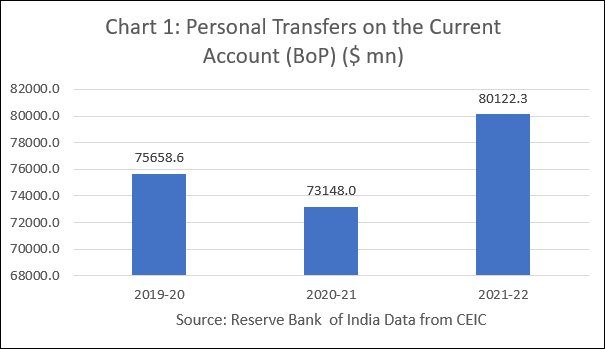

This buffer can be critical in times of balance of payments strain. Fortunately, balance of payments data from the RBI suggest that remittance inflows have been relatively strong through the pandemic. Having fallen by 3 per cent, from $76 billion in pre-pandemic year 2019-20 to $73 billion in 2020-21, these flows bounced back to touch $80 billion in 2021-22 (Chart 1). Though there was some slippage, the impact of the pandemic on this indicator was not as damaging as in other areas of economic activity.

However, according to figures recently released by the RBI, the pandemic did change the source countries from which these remittances originated. Since 2006 the RBI has been conducting periodic surveys of intermediaries channelling recorded remittances into the country. Till the third survey relating to 2012-13 the exercise was restricted to banks that as authorised dealers (ADs) in foreign exchange were mediating the inflows. For the two most recent surveys, besides the ADs, three major money transfer operators (MTOs), which are important channels for transfer from the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, because they are more user friendly and cost effective, were included. This does affect comparability of the figures from the first three and the next two surveys, but comparisons of broad trends indicated are still tenable.

The first three surveys established quite clearly what has been known for some time: that the Gulf Cooperation Council countries of West Asia were as a region the dominant source of remittances into India. Ever since the oil price increases of the 1970s set off a construction and business boom in the Gulf, those countries have been the destination for a migration trail of workers from India, varying from the unskilled to the semi- and highly skilled. Being migrants holding time-bound visas, often without permission to take their families with them, these workers had to repatriate money to finance household consumption at home and transfer sums for any investments undertaken.

But soon this stream of remittance flows was augmented by another stream to destinations other than the Gulf predominantly to the United States and the United Kingdom. These were temporary workers employed to provide software and business services on location, often sent by firms in India taking on offshored contracts to provide onsite support services. These workers too sent money home to support consumption needs and finance investments out of savings. This increased the volume and share of remittances originating in the advanced economies (AEs), especially the US.

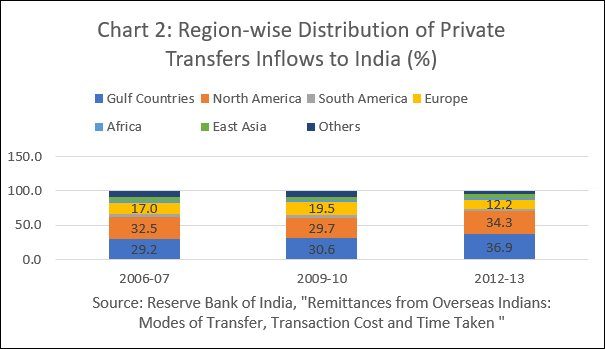

However, the evidence from the first three surveys of inward remittances showed that the Gulf countries as a group, having lost ground during the early years of the software services boom, restored their position as the single largest source of remittances. The share of the Gulf countries in private transfer inflows rose from 29.2 per cent in 2006-07 to 30.6 per cent in 2009-10 and 36.9 per cent in 2012-13. On the other hand, the North American share in these three years was 32.5 per cent, 29.7 per cent and 34.3 per cent, and the European share 17, 19.5 and 12.2 per cent (Chart 2).

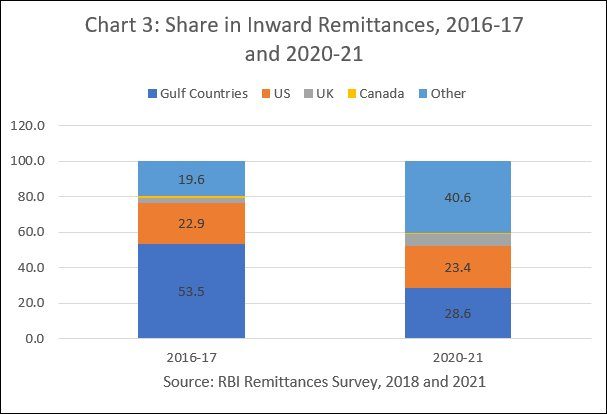

Given the inclusion of three major MTOs in the channels surveyed, the results from 2016-17 and 2020-21 were substantially different. Thus, in 2016-17, the RBI survey indicated, the GCC countries accounted for as much as 53.5 per cent of inward remittances to India. This compared with just 26.9 per cent for the US, 3 per cent for the United Kingdom, and 1 per cent for Canada (Chart 3). Clearly, the earlier survey had underestimated the importance of the GCC countries as sources of remittances into India.

However, the most recent data relating to pandemic year 2020-21 suggests that the collapse in oil prices and trade volumes hugely affected remittances from the Gulf. In that year the share of the GCC nearly halved to just 28.6 per cent (from 53.5) whereas the share of the US edged up marginally to 23.4 per cent (from 22.9) and that of the UK more than doubled to 6.8 per cent (from 3 per cent) (Chart 3). Since the figures quoted earlier suggest that overall private transfers came down by just 4 per cent from $76 billion to $73 billion in that year, it must have been the case that absolute flows from the US and UK either remained relatively stable or even rose. It is not clear why the share of the residual category “other countries” registered a sharp rise, but it does appear that flows from the Gulf were hit badly.

The relative resilience of overall flows and those from the US and UK is possibly explained by the fact that in a crisis period when short term migrants lose their jobs and return home, they make lump sum transfers of the savings held abroad. Since skilled software and business services providing workers are likely to earn and, therefore, save more, those bulk transfers were probably larger from the US than the GCC. The only issue here is that since movement across borders, and therefore of the return home of migrant workers, was curtailed during the first year of the pandemic, it is not clear whether this process would have unfolded in full in 2020-21. But it is possible that workers began transferring their savings in preparation of their return.

While the details need investigation, the figures do suggest that remittances resulting from migration of the type characteristic of the GCC countries are far more volatile than those from the advanced economies. Given the importance of remittances for India’s balance of payments, this is a source of instability that needs to be taken account of. More so because of the possibility that the progress of climate negotiations and climate action, leading to the phase down of fossil fuel production and consumption, may bring to an end the unusual boom in the Gulf since the 1970s, which benefited countries like India through migration and the resulting remittances.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on January 24, 2023)